Joe Overstreet: Taking Flight is the first major museum exhibition in thirty years devoted to the work of this pioneering abstract painter. Renowned for his innovative approach to non-representational painting, American artist Joe Overstreet (1933–2019) consistently sought to intertwine abstraction and social politics. This presentation will include his landmark Flight Pattern series of radially suspended paintings from the early 1970s, as well as related bodies of work from the 1960s and 1990s. Overstreet made a significant contribution to postwar art, positioning abstraction as an expansive tool for exploring the idea of freedom and the Black experience in the United States.

Miriam Schapiro: 1967–1972 features a concise selection of Schapiro’s monumental paintings, examining a crucial period of development in the work of the legendary feminist artist. The works on view from this time see Schapiro’s hard-edge geometric abstraction evolve into her gendered, anthropomorphic “central core imagery” and lay the groundwork for her explorations of collage and craft within the Pattern and Decoration movement. The exhibition showcases Schapiro’s pioneering work exploring early digital image production technologies, presaging contemporary artists’ practices today in the realm of feminist and digital art.

Sixties Surreal is an ambitious, scholarly reappraisal of American art from 1958 to 1972, encompassing the work of more than 100 artists. This revisionist survey looks beyond now canonical movements to focus instead on the era’s most fundamental, if underrecognized, aesthetic current—an efflorescence of psychosexual, fantastical, and revolutionary tendencies, undergirded by the imprint of historical Surrealism and its broad dissemination.

Throughout a career spanning six decades, Nina Yankowitz (American, b. 1946) has created a multidisciplinary practice that defies singular definition. Her work pushes against traditional boundaries: her paintings have resisted not just frames, but seemingly gravity; her abstract compositions have gone beyond the canvas to embrace the aural. Most recently, Yankowitz has deepened her interest in technology and new media to create immersive environments that spotlight women-centered histories that have gone unknown for far too long.

Nina Yankowitz | In the Out/Out the In will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg from June 21 through September 21, 2025. The exhibition will then travel to The Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY, where it will be on view from October 5, 2025 – February 22, 2026.

Until his final years, Joe Overstreet (1933–2019) worked at Kenkeleba House, an East Village arts organization providing a gallery and studios, which he founded in 1974 with his future wife, curator and historian Corrine Jennings, and writer Samuel C. Floyd. I was fortunate to once visit Kenkeleba House with artist David Reed and witness both Overstreet’s studio and the extensive and impressive archive of work by Black American artists collected and housed at the institution. Knowing this background, it was thrilling to encounter the current exhibition, Taking Flight, at the Menil Collection and see Overstreet’s works so dynamically and meticulously presented. Three major series of paintings sequentially unfold across several generously sized gallery spaces. The height of the ceilings also allows for the placement of works in relation to each other in ways that emphasize Overstreet’s pioneering use of space for exhibiting visual art. Color, pattern, and three-dimensionality meld together effortlessly and inventively.

"The show’s sensuality is a release: Amid so much fear and suffering, there’s still plenty of pleasure to be found."

Moderated by Rachel Middleman

With Martha Edelheit, Jenna Gribbon, Keith Mayerson, Sur Rodney (Sur), & Didier William

The Wright Museum presents a collaborative gathering of over sixty artworks. Works by present-day Detroit artists, long departed masters, and selections from the museum’s archives are placed in stunning visual and aural dialogues. Arcing across six decades, the artworks’ collective radiant energies unfold in a vibrant visual landscape marked by startling tensions, and at times, a confounding powerful stillness.

Review of Joe Overstreet: Taking Flight, at the Menil Collection, Houston, January 24 – July 13, 2025.

Here is the definition of erotic, according to 93-year-old artist Martha Edelheit. “It’s sensual, nonviolent, consensual, warm, inviting, sometimes funny, witty, amusing. Erotica assumes shared association, touching, stroking, licking, looking, playing, exposing. It digresses, teases, laughs, arouses, without harming.”

This is all further laid out, to vivid effect, in “Erotic City,” a group exhibition of more than 40 artists from the 1950s to the present, including Joan Semmel, Carolee Schneemann, Paul Cadmus, and Tom of Finland, on view now through April 26 at Eric Firestone Gallery at 40 Great Jones Street.

Peter Williams featured in AUTHORITY PROBLEM, a group exhibition that explores notions of authority – from its meaning as “expertise” and legitimate institutional authority, to abuses of power and the role of protest in the face of the current global turn toward authoritarianism.

The words “erotic art” mean different things to different people. Ideas of just what that entails might range from ancient Greek statues of the sex goddess Aphrodite to Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde to the semi-abstract paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe. The category is quite pliable and open to creative interpretation, a fact that curator and artist Martha Edelheit has put to good use at the new exhibition Erotic City, opening at Eric Firestone Gallery in New York.

April 4, 1968, was a day of mourning for nearly every American, with an outpouring of grief following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. by a white supremacist. April 5, 1968, was the day painter Joe Overstreet began work on Justice, Faith, Hope, and Peace (1968), a four-panel shaped canvas that encapsulated the mood of the moment.

Two diamond-shaped panels, with targetlike forms rendered in raucous shades of red and orange, lie at the center of this painting; they are bookended by a pair of rectangular panels painted with symbols that recall blasts, their pointed cerulean forms blown apart by jagged shapes. Despite its cheerful colors, the painting suggests violence and upheaval.

Justice, Faith, Hope, and Peace is aptly placed at the start of a terrific exhibition of Overstreet’s work at the Menil Collection in Houston. It is an overdue survey for the late artist, who has gone overlooked by major museums in this country for far too long. The 30 or so paintings assembled here are variations on a theme: They propose abstraction as a path toward liberation.

We Loved the Swag: From Black Bottom Until Now focuses on artist Judy Bowman’s experience growing up on the Eastside of Detroit. During the mid-20th century, the eastside neighborhood known as Black Bottom was the heartbeat for Black families—a neighborhood thriving with jazz, entertainment, businesses, and community.

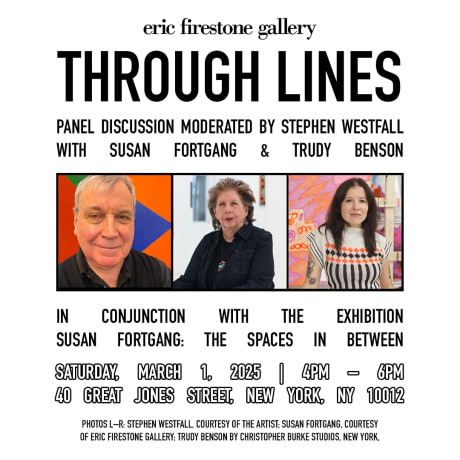

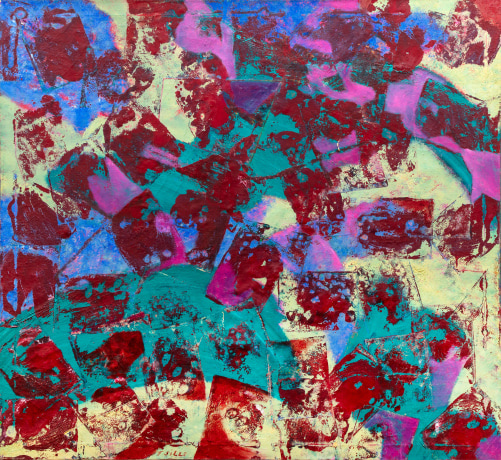

Though Susan Fortgang has shown her art intermittently since getting an M.F.A. at Yale in 1968, and was included in “Pattern Painting,” an influential group show at P. S. 1 in 1978, “The Spaces in Between” at Eric Firestone Gallery is her first official solo exhibition. It includes a couple of large, gestural abstract paintings from the 1960s, but since the late ’70s, Fortgang has been using rules, grids, tape and thick layers of acrylic paint to make brightly colored, geometric works that look very much like textiles.

RicanVisions aims to continue to expand the canon of Diasporican visual art, bridging the past and present of contemporary art from the Puerto Rican diaspora. The exhibition includes emerging artists, some who are showing in New York City for the first time, as well as veteran artists overdue for recognition, such as Marina Gutiérrez and the abstract artist Evelyn López de Guzmán who are showcasing work that has never been exhibited before. Some of the artists were selected through their participation in the annual Artist-in-Residence open call at The Latinx Project.

Miriam Schapiro's Fanfare (1958), Collection of the Jewish Museum, is on view in Masters of New York: The Generation of Rothko, Pollock, and Krasner.

Please join us for light holiday refreshments starting at 5:30 pm, followed by a Q&A with the artist and Associate Director Maddy Henkin.

The exhibition has been extended through January 10, 2025.

Please join us for a curator-led walkthrough of the exhibition at 2pm, followed by a Q&A and reception.

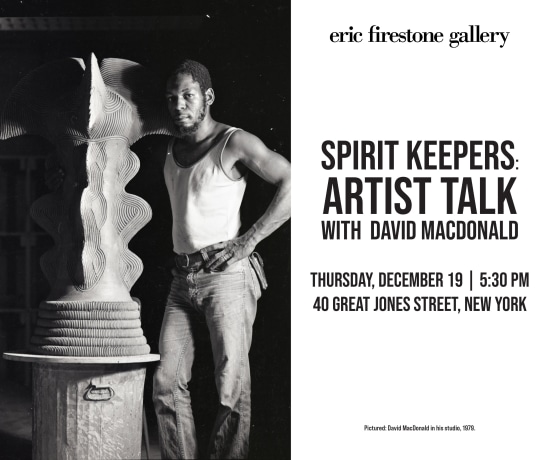

The uplifting and complex "Spirit Keepers" is now on view at New York's Eric Firestone Gallery. The trio of artists use color and form to reach for a higher power.

The claim that painting is dead has been a common refrain among critics for decades. Nevertheless, artists have continuously pushed the medium forward. The Living End: Painting and Other Technologies, 1970–2020 surveys the arc of painting over the last 50 years, highlighting it as a mode of artistic expression in a constant state of renewal and rebirth.

The Way I See It: Selections from the KAWS Collection features more than 350 artworks chosen by KAWS from his vast personal collection of over 3,000 works on paper by some 500 artists. The Way I See It continues The Drawing Center’s tradition of exhibiting drawings from outstanding public and private collections, and offers an unprecedented glimpse into the artistic inspirations and interests of one of today’s most popular contemporary artists.

Edges of Ailey is the first large-scale museum exhibition to celebrate the life, dances, influences, and enduring legacy of visionary artist and choreographer Alvin Ailey (b. 1931, Rogers, Texas; d. 1989, New York, New York).

In conjunction with the exhibition Across the Pond: Contemporary Painting in London.

Bringing together more than ninety works spanning six decades, Electric Op examines how artists have used abstraction to explore the relationship between perception and technology. While today considered an art historical “dead end” with few echoes in contemporary art, Op art in fact became the first artistic movement of the Information Age, paving the way for art to be abstracted into analog and digital circuits. Just as optical illusions help us “see” ourselves in the act of seeing, Op art can help us see how vision itself has been transformed by electronic media.

Most recently, it was Eric Firestone Gallery that began working with Futura to reintroduce him to the art world proper in 2020. What the gallery recognized was that beyond his reputation in the graffiti world, Futura was and is an artist with a decades-long studio practice.

Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960-1991 surveys the history of digital art from a feminist perspective, focusing on women who worked with computers as a tool or subject and artists who worked in an inherently computational way.

The exhibition features Miriam Schapiro's The Palace at 3:00 AM or Meander (1971).

“Stories of Place” draws on the rich range of artwork recently acquired by the Museum including collage, sculpture, photography, painting, and quilts. The selected works on view provide opportunities to reflect on the diverse meanings of “place” in the visual arts and in storytelling.

Particles and Waves examines how concepts and technologies from the realms of advanced scientific research impacted the development of abstract (or non-figurative) styles of artwork in postwar Southern California.

FUTURA 2000: BREAKING OUT is a retrospective of this singular artist’s evolution from early graffiti art styles to his current practice of contemporary abstraction. The exhibition is the most comprehensive examination of FUTURA 2000’s five-decade career ever presented in his hometown of New York City. On view from Sunday, September 8 through winter 2025, BREAKING OUT showcases his sculptures, drawings, prints, studies, collaborations, and archival paraphernalia dating from the 1970s to the present, as well as new site-specific temporary installations.

In East Hampton, Eric Firestone Gallery opens a sprawling show of bold and elaborate works by 22 artists. Loosely themed around optimism, Alright Alright Alright is a showcase of pattern, material, and color that feels high-energy and offers a little jolt in the slowest part of summer. Kelsey Brookes’s kaleidoscopic sewn Indian tapestries and the pristine lines of automotive paint on maple wood by Jason Middlebrook are intricate and hypnotic. Among the more geometric, abstract works, notably the engrossing Ellsworth Ausby, there are some irreverent and intriguing characters, one-eyed with bubble-flip hair or with no face at all, the work of New York–based Bruce M. Sherman, who makes pieces out of ceramic, metal, and rock. Closes September 22.

Legendary artist, Paul Waters, dives into his beautiful yet grueling life as an artist. Sammy Loren joins him in his studio to delve into Waters’ extraordinary journey from post-war obscurity to relentless pursuit of artistic expression.

“Community works here in a way that they take notice if you’re accessible or if you’re not accessible,” Firestone told Artsy. “I’ve never hidden behind a wall. I don’t sit in an office and wait to come out for the right people.”

The 6 artists in All The Things defy the conventions of traditional painting. They adeptly blur the boundaries between "support" and "surface," employing techniques such as manipulating stretcher bars, cutting canvas, and integrating diverse materials to construct their artworks rather than solely relying on paint. Drawing inspiration from elements of drawing, collage, and sculpture, these artists not only push the limits of painting but redefine its language.

The Church’s summer 2024 exhibition considers humor and contemporary art, focusing solely on the work of female-identifying artists. Conceived and organized by Chief Curator Sara Cochran, it features the work of 40 artists across all media installed across The Church’s Main Floor and the Mezzanine.

Eric Firestone Gallery would like to welcome the public to the closing and catalog release party of Lauren dela Roche: No Man's Land and Cato: Love Song on Wednesday, June 26, 6–8PM.

Having dropped out of high school, left an abusive relationship, escaped a Pentecostal cult, and uncovered her repressed sexuality, and all before the legal drinking age, Lauren dela Roche felt aimless at twenty-three. Untethered to few places or people, she moved to her family’s wooded farmland in East Central Minnesota—property acquired by her Swedish potato farming ancestors in the 1800s—arriving with little more than a few pairs of clothes and a machete. Seven years later, she was living in a straw bale cottage she had constructed from the ground up, and sustaining herself off food she had grown in soil composted with her own manure.

In preparation for her first solo show at Eric Firestone Gallery, on view through June 29, dela Roche seized the same grit, fortitude, and commitment to self that building a house and a life from the earth requires.

Naked women lounge across cotton feed sacks mounted on stretcher bars in “No Man’s Land,” the self-taught painter Lauren dela Roche’s debut show with the Eric Firestone Gallery. Their heads all have the same dark hair and fine features, as if copied from the cover of a single Victorian calendar, and are two or three sizes too small for their statuesque bodies. An unbroken vista of fountains, butterflies, flowers, shallow tunnels and swans with chili-pepper beaks extends behind them.

With Talk Art Podcast, KAWS aka Brian Donnelly discusses his three major institutional exhibitions all opening in 2024. The first show has just opened at The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh and is the first time that Donnelly's work has been aligned with Warhol. Followed by the Parrish Art Museum this summer, and The Drawing Center, set to open in Autumn.

The artists in Skilled, Subversive, Sublime: Fiber Art by Women mastered and subverted the everyday materials of cotton, felt, and wool to create deeply personal artworks. This exhibition presents an alternative history of twentieth-century American art by showcasing the work of artists who, stitch by stitch, utilized fiber materials to express their personal stories and create resonant and intricate artworks.

Non-Objectified presents a dynamic group of works by female artists operating under the umbrella of abstraction. The show’s title is a play on the term ‘non-objective’ painting, coined by by Alexander Rodchenko in 1918. This movement was centered in Europe and created in reaction to centuries of figurative representation, as practiced and espoused in the academies. Non-Objectified is a riff on Rodchenko’s term, a double entendre exploring female artists’ resistance to the objectification of bodies. The show takes the form of a dialogue between works by a cross-generational, international group of artists selected for their varying approaches to abstraction, each variation invoking or involving the body in subtle ways.

The Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation is pleased to present Pat Passlof: Authors & Poets, 1999-2000. The exhibition is on view May 9 - July 20, 2024.

The paintings came first—the titles came after.

Lauren dela Roche is growing, literally. In preparation for her first New York solo show, on view at Eric Firestone Gallery through June 15, the Missouri-based artist shut herself in the studio for months, working away at the dense feed-sack frescoes she is making her name with. Her one extracurricular? Weightlifting. “My whole life I have tried to be really small, like physically really small,” she tells me over the phone. “I’ve tried to restrict my eating and never gain weight. I'm trying to take up space for the first time in my life. And I think that's the only reason I was able to make a big painting.”

That ’70s Show and Esther are not only authentic community builders, but become visual collective memories thanks to their theme and scale.

Season 2 of the wildly successful mini fair returns to Eric Firestone’s loft this year, with a showcase of 18 stalwart galleries presenting works by artists who were active in the titular ’70s. Look out for New York favorites Ryan Lee, Ortuzar Projects, Karma, Andrew Kreps, and Franklin Parrasch, plus host Eric Firestone, all bringing interesting and oft-overlooked artists who were integral to their local art scenes of the decade.

For the second year in a row, far from Frieze New York in Hudson Yards, the SoHo art dealer Eric Firestone is hosting 18 New York galleries, all of whom are celebrating the 1970s.

The micro fair, organized by the dealer Eric Firestone (and on view in his walk-up loft), returns for its second year. That ’70s Show bills itself as an “alternative” to the fairs of Frieze and as a community of artists who celebrate one another. This year it will feature 18 New York galleries presenting artists who created work during the 1970s. Entry is free. May 2–5 at 4 Great Jones Street, Manhattan; 70sshownyc.com.

Judging by Eric Firestone’s recent programming (woe to New Yorkers who missed a recent show about the Godzilla collective), the gallery gets what means success for a group show. No color, pattern, or material overstays its welcome; each addition enriches the lot, all in service of a grand purpose. The gallery’s booth at Expo is much of the same, a vibrant medley of paintings, ceramics, and collages. A 1967–70 painting from Regina Granne is among the more interesting nudes on the sales floor, and a 2024 black and white collage from Cato, a London-based artist and musician, is a promising teaser for his forthcoming show at the gallery.

Sana Musasama: Returning to Ourselves centers around a series of dolls, based on African-American topsy turvy dolls. Musasama uses this formal structure to juxtapose figures drawn from the global Black diaspora. Returning to Ourselves is rounded out by a series of ceramic houses she began early in her career and returned to during the pandemic.

The legacy of Ishirō Honda’s 1954 cinematic triumph, “Godzilla,” extends far beyond the big screen. Unfolding against the backdrop of post-war Japan, devastated by atomic bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a dormant leviathan, mutated by nuclear testing, emerges from the Pacific Ocean and wages war against humanity. For a group of Asian American artists reckoning with the exclusionary policies and lack of representation in the art world in 1990, Godzilla became a fitting moniker. The metaphorical resonance of the anarchist lizard’s emergence, reflecting the consequences of nuclear testing and the struggle for recognition, mirrored the artists’ own challenges and their determination to reform the tide of hegemonic American consciousness.

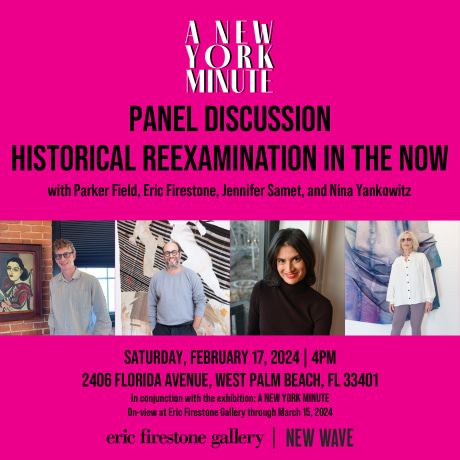

With Parker Field, Eric Firestone, Jennifer Samet, and Nina Yankowitz.

In conjunction with the exhibition A New York Minute The exhibition is presented in partnership with New Wave, a non-profit arts organization founded by Sarah Gavlak. On view at Eric Firestone Gallery, 2406 Florida Avenue, West Palm Beach, Fl 33401, through March 15.

The short month of February still packs a lot of art in New York City, from a survey of the influential Godzilla Asian American Arts Network to Apollinaria Broche’s whimsical ceramics and Aki Sasamoto’s experimentations with snail shells and Magic Erasers in her solo show at the Queens Museum.

In conjunction with the exhibition Godzilla: Echoes from the 1990s Asian American Arts Network.

Moderated by Ryan Lee Wong, with Helen Oji, Charles Yuen, and Bing Lee. Held in conjunction with the exhibition Godzilla: Echoes from the 1990s Asian American Arts Network. On view at Eric Firestone Gallery, 4 + 40 Great Jones Street, New York, through March 16.

A second panel discussion in conjunction with the exhibition will be held on March 9 at 3:00 PM, details to come.

Odes to tea, kung fu and fortune cookies, as well as sly responses to racism, sexism and negative stereotypes swirl through the works in Godzilla: Echoes From the 1990s Asian American Arts Network, a two-venue show featuring 39 artists. The title refers to the collective Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network, which was founded in New York in 1990 to support Asian American artists of different backgrounds.

The Maverick Legacy of Godzilla Asian American Artists Network

An exhibition at Eric Firestone Gallery spanning the late 1980s to present day delves into their multidisciplinary output.

We are pleased to announce that Shirley Gorelick’s Family II (1973) has been acquired by the Brooklyn Museum as part of the museum’s permanent collection.

In conjunction with the exhibition Pat Lipsky: Color World

We are pleased to announce that Pat Passlof’s Ile Fra (1960) has been acquired by Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art as part of the museum’s permanent collection.

held in conjunction with the exhibition Elise Asher: The Vintage Years Paintings of the 1950s and '60s

On his birthday, the artist looks back at his singular journey from graffiti writer to industry game-changer.

This exhibition is the first of two consecutive installations featuring the closely related techniques of collage, assemblage, photomontage, and found object sculpture. The diverse selection of artworks by leading national and international artists, drawn from Mia’s collection and local private collections, emphasizes the museum’s commitment to modern and contemporary art. The exhibition examines the resurgence of interest in these art forms during the postwar period and ensuing decades, highlights both formal and conceptual experimentation, and demonstrates how these interrelated techniques are particularly suited to exploring social, political, cultural themes and content.

Each year, the popular "Meet the Artists" event allows visitors to the fair to learn more about exhibitor presentations from artists whose work is on view and from experts associated with historical presentations.

Eric Firestone has made a career of rescuing artists from the dustbin—or at least the margins—of art history, particularly New York in the late 20th-century. Here he’s featuring five who appeared in important exhibitions devoted to Black art in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Paul Waters’s canvases have a gorgeous, geometric simplicity, but the real standout is Anderson Pigatt, a self-taught sculptor who also worked as a restorer of antique furniture after studying cabinetmaking on the G.I. Bill. In Honor of the Brothers and Sisters of Reclamation Site One (1969) is a hulking monument made from a fallen oak tree in a Harlem park. The idea that wood has a spirit is deftly translated in this tough-but-tender memorial to civil rights activists.

The first career retrospective in the United States of the seminal New York City-based artist opened this weekend at UB Art Galleries. The exhibition, FUTURA2000:Breaking Out, spans the vast output of an artist who rose to prominence with aerosol can-propelled graffiti and street painting in the 1970s and ‘80s, evolving into painting on canvas, sculpture, wall murals, and product design and high-end fashion.

Blum & Poe, Los Angeles is pleased to present “Pictures Girls Make”: Portraitures, an exhibition bringing together over fifty artists from around the world, spanning the early nineteenth century until today. Curated by Alison M. Gingeras, this prodigious survey argues that this age-old mode of representation is an enduringly democratic, humanistic genre.

The power of an artwork is often amplified when in dialogue or debate with another. It Takes 2: Unexpected Pairings explores the resonances and dissonances that arise when unrelated objects are set side by side.

The works of three late women abstract artists were the subject of New York gallery Eric Firestone’s Frieze Masters display, a smartly curated booth that pays tribute to a group that has gained a long-overdue reappraisal in recent years. “The booth really evokes the mission of the gallery, which is to focus on reexamination and scholarship, primarily of American artists,” Firestone told Artsy. The artists on view—which the gallery represents the estates of—certainly belong in that category.

Lauren dela Roche's Caterpillar (2023) illusrates poem by Laura Kolbe in Harper's Magazine, September issue.

Women Artists and Collectors Are at the Fore of the Hamptons Art Scene. Here Are 6 Female-Focused Exhibitions to See Into September: Here's a rare chance to glimpse into the blue-chip collections of some of the world’s top female collectors.

This August Eric Firestone Gallery is presenting a two-part exhibition across its East Hampton and New York City locations. The Hamptons iteration of (Mostly) Women (Mostly) Abstract features a cross-generational group of 22 experimental post-war artists, often on the fringes of the mainstream art world. “The show delves into the works of contemporary artists and their predecessors, who practiced abstract art and explored otherness in this genre—themes such as ethnicity, race, gender, and sexual orientation, which are as relevant now as ever,” gallerist and curator Eric Firestone told Artnet News. Though the artists are separated by time and experiences, their “intensely graphic work and saturated colors” form a cohesive narrative.

As the title suggests, a roster of mostly women artists can be seen on view, alongside other creatives working in abstraction, whose art aligns with the subject matter at hand—including those like Sally Cook, Judy Pfaff, Helen O’Leary, Jenny Snider, Despina Stokou, Reginald Madison, Keiko Narahashi, Pam Glick, and Kennedy Yanko, to name a few. Works on view span at least 50 years, creating a dynamic and energetic display of textures, surfaces, and dimensions that lead the viewer on a thoughtful journey of otherness to wonder, “What defines abstraction?”

University at Buffalo Art Galleries is pleased to present FUTURA2000: Breaking Out, a retrospective of artist FUTURA2000 that will span both University of Buffalo Art Galleries locations; UB Center for the Arts and the UB Anderson Gallery.

Over his career span of five decades, FUTURA has built a reputation and continues to be an unrelenting innovator. He has inspired and influenced multiple generations of creative purists and polymaths while intersecting his enigmatic oeuvre with various disciplines and remains at the forefront of the cultural zeitgeist. FUTURA2000: Breaking Out is a comprehensive survey featuring paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, studies, collaborations, and archival paraphernalia. The exhibition will also feature new site-specific works. Breaking Out examines one of New York's most-loved artists' essential themes and polyphonic output.

At their core, creating and looking at works of art are acts of care, from the artist’s labor to the viewer’s contemplation and appreciation. Storage, conservation, and display are also ways of tending to art. This exhibition invites visitors to explore how contemporary artists trace and address concepts of care through their materials, subjects, ideas, and processes

What Has Been and What Could Be: The BAMPFA Collection inaugurates a year-long presentation of the BAMPFA collection, bringing a contemporary perspective to the museum’s global art holdings.

Femininity and summer are at the forefront of this new East Hampton show. It gives viewers the opportunity to celebrate the season—embodied in florals, sunbeams, and beach scenes. Work from 15 different artists, among them Sylvia Sleigh and Robert De Niro Sr., will be on display, and the show includes pieces from artists Eric Firestone is showing for the first time, like Lauren dela Roche and Elise Asher. Beauty of Summer will be on view through July 30, 2023 at Eric Firestone Gallery in East Hampton.

Self Portrait Five Images is one of several standouts in “Where Fantasy Has Bloomed, Painting and Poetry since the 1960s,” an excellent survey of Cook’s work on now through July 8 at Eric Firestone Gallery in New York. Included is work from three decades of her career—a time period that saw her switch styles, cities, and priorities. It expands on an exhibition that opened at the University of Buffalo Art Galleries in mid-March of 2020, only to be shuttered by the COVID-19 pandemic days later.

Salon Summer 2023

Eric Firestone Gallery, The Garage 62 Newtown Lane, East Hampton, NY

Featuring a new installation combining historic material represented by the gallery, and younger generations of contemporary artists, this 7,000-square-foot open warehouse space was recently renovated with specially designed, large moveable walls to create exciting exhibition possibilities. The gallery hopes that the Salon installation will encourage viewers to spend extended time looking as they visually showcase and highlight the gallery’s mission: “an ongoing reevaluation of the art historical canon, and its legacy and influence on younger artists.”

Jeanne Reynal, A Good Circular God, 1948–50, is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in 2023.

"Despite its relatively modest profile, as an art experience I think That ’70s Show will stick around in my head longer than Frieze. Maybe there’s just a certain organic fit between the concept, the art on view, and the venue—all are kind of scrappy and off-the-beaten-path and so worth championing."

Sana Musasama at Eric Firestone Gallery Booth 8

Across the hall, we were drawn to Eric Firestone Gallery's solo presentation of Sana Musasama's sculptures hanging on the wall, as well as ceramics displayed on tabletops. For the show, the Brooklyn-based African-American feminist artist and activist showed works that reflected her mantra, "Inspire, Commit, Act," including new and existing pieces across several series. They are also in dialogue with furniture and design items from her personal home and studio in Queens, as well as pieces she's collected over years of international travels.

Get Out Your Checkbook, It's Frieze Week-Month in Manhattan

Another pleasant surprise was a very serious fair with an extremely silly name: That ’70s Show. No, it has nothing to do with the Topher Grace–Ashton Kutcher sitcom; it’s just a cool micro-fair where local galleries brought a few works and installed them in Eric Firestone’s two loft-through spaces at 4 Great Jones Street. All the works in the show were made in the 1970s, many of them by artists who lived in the neighborhood, in SoHo and NoHo, in semi-legal apartments.

Sana Musasama at Eric Firestone Gallery Booth 8

New York’s Eric Firestone Gallery is showing a solo booth of ceramic works by Sana Musasama, an African American artist who has been working since the 1970s, drawing inspiration from her activist work with international communities of women. On the first day, four works had been sold to “significant private collectors,” the gallery’s director said, including a large standing sculpture from the artist’s “Maple Tree Series” (1979–83), as well as smaller works that dot the booth’s walls.

That 70s Show, a 20-dealer takeover of Eric Firestone Gallery’s loft space at 4 Great Jones Street in New York, spotlights artists who were active during the titular decade, a period of enormous growth and experimentation across genres and media. The thematic fair (until 21 May) was inspired by a lecture given by the critic Jerry Saltz about the importance of keeping the legacies of older artists prominent in the cultural consciousness, after which dealer Eric Firestone resolved to “disrupt the usual fair week”, gathering a large variety of works from a pivotal moment in the New York art scene. Galleries participating in the project include PPOW, Karma, Kasmin, Ortuzar Projects, Craig Starr Gallery and Gordon Robichaux, among others.

Tucked into the third and fourth floors of an old building on Lower Manhattan’s Great Jones Street, an expansive gallery exhibition is paying homage to the 1970s. Running through Sunday, May 21, That ’70s Show is a refreshingly free alternative to this weekend’s astronomically priced art fairs. It includes presentations by 21 galleries, all featuring work from the decade of the shag carpet. The two upper-level loft spaces are part of Eric Firestone Gallery, which has its primary storefront a few blocks away on the same street. All three spaces are in Soho, the bohemian hub of 1970s New York.

In a project organized by the dealer Eric Firestone, 21 galleries will exhibit works by artists who were active in the 1970s. Calling itself an “alternative” to the fairs of Frieze, the show—on display in his walk-up NoHo loft—pays tribute to galleries invested in scholarship and the re-examination of artists from that decade. Entrance is free. May 18–21 at 4 Great Jones Street, Manhattan; 70sshownyc.com.

There’s an outsized emphasis on newness during Frieze week. But this week, 21 dealers will ignore the new and instead look 50 years back in time. This is the precept behind That‘70s Show, a joint presentation of work from the 1970s by 21 New York galleries, including Bortolami, Karma, Kasmin, Lyles & King, and Ortuzar Projects. From May 18–21, they will set up shop across two lofted floors at Eric Firestone Gallery on Great Jones Street, a raw, light-filled space that itself feels like the downtown art world of yesteryear.

Twenty-one New York galleries are presenting an alternative to Frieze in the form of a throwback exhibition well worth the 20-minute trip from the mega-fair. Anton Kern, Bortolami, PPOW, R & Company, Venus Over Manhattan, and Kasmin are just a handful of those contributing ‘70s-era works to the group showing, which its organizer, Eric Firestone, is hosting at his loft space on Great Jones Street. You’d think they’d want to make the most of all that organizational effort, but this ‘70s show won’t be back for reruns. It’s on view from May 18 through 21, then it’s gone.

With two weeks worth of art fairs in New York, from Independent to Frieze, the city is about to add one more, a new initiative called That ’70s Show. Organized by dealer Eric Firestone during the past month, 20 dealers will take over Firestone’s loft space on 4 Great Jones Street to show works from artists who were active in the 1970s. Spread across two floors, the galleries lined up to participate include P.P.O.W., Karma, Kasmin, Ortuzar Projects, Craig Starr Gallery, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, Anton Kern Gallery, and Gordon Robichaux.

Eric Firestone Gallery, a well-known New York gallery that has been following abstract art in the 20th century, participated in Taipei Contemporary Art Fair for the first time, and introduced five mid-century abstract female artists from New York. One of them, Pat Lipsky (b. 1941), is famous for exploring the color gamut painting. The large-scale work Winter used back and forth smudged brushwork and harmonious tones to express her lyrical and abstract skills. You can also see the rhythm of her body in the picture. Staring at the picture is like seeing the endless ocean in winter, waiting alone for a ray of hope.

There is no doubt Miriam Schapiro has received more attention and accolades in recent years than she had in the later period of her life. However, the urge to pigeonhole her into strictly feminist art movements, which many have, misses entire aspects of her creative output and her prescient and revolutionary approaches to new technology and art making.

At a panel discussion on April 26, conducted by Zoom from the Eric Firestone Gallery in downtown Manhattan, artists and art historians attempted to define her contributions in a more holistic sense and ask the important question of why she hasn't received her full due.

In the days before smart phones and email, people hand wrote contact information in books designed for that purpose. Telephone numbers were prefixed by two-letter abbreviations for exchanges, such as Butterfield (BU), Chelsea (CH), Trafalgar (TR) and Plaza (PL). Three such books belonging to Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner have survived: two are among their papers in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art; one is owned by the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center. All three books will be on view, together with some 30 works by artists whose names, addresses, and telephone numbers appear in them.

This exhibition—the first in the Museum’s history to have been fully developed and curated by an undergraduate student—features more than 50 contemporary artworks by women artists, with an emphasis on works created with unusual techniques or media.

Nina Yankowitz takes over an entire gallery to literally offer alternate perspectives for experiencing art: Reclining lounge chairs invite viewers to look up at works by Tara Donovan, Rashid Johnson, Louisa Chase, Mary Heilmann, and Vija Celmins; a 7-foot platform allows a view from above of a visual sound score woven into a rug. Seated in a heavy chair with tiles, viewers confront Chuck Close‘s self-portrait, while small works hang at tilted angles in the distance. Yankowitz chose works relevant to life in America today, including Jackie Black’s Last Meal (Series), 2001–2003, 24 photographs of meals requested by death-row inmates, paired with Yankowitz’ uncanny sculptural paintings of body parts protruding from the wall to imagine “what’s on the other side.”

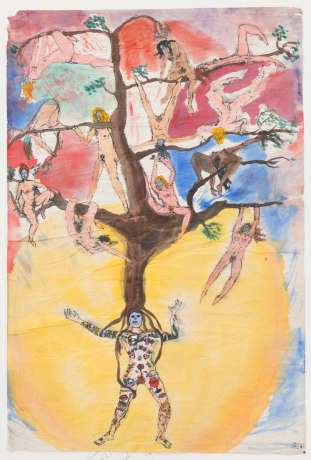

David Zwirner's group exhibition So let us all be citizens too explores and celebrates the legacy of post-war American artist Bob Thompson (1937–1966) and his dynamic figurative style and use of colour. Bringing together contemporary international artists of several generations whose aesthetic affinities to Thompson are both discernible and surprising, the exhibition includes paintings and works on paper by Emma Amos, Michael Armitage, Betty Blayton, Vivian Browne, Beverly Buchanan, Lewis Hammond, Cynthia Hawkins, Marcus Jahmal, Danielle Mckinney, Cassi Namoda, Chris Ofili, Naudline Pierre, George Nelson Preston, Devin Troy Strother, and Peter Williams.

One of only a few African American participants in the abstract expressionist movement, Thomas Sills (1914–2000) has been largely overlooked until recently. Donated by John Pappajohn to the National Gallery of Art, the painting Flagship (1963) epitomizes the distinctive style and technique Sills developed to create elegant abstractions with a limited palette and disciplined forms.

Described by Monica Ramirez-Montagut as a "homecoming" for artists who have worked with the Parrish Art Museum over the years, the museum's 125th anniversary celebration has officially begun, with the first iteration of its "Artists Choose Parrish" series of exhibitions now on its walls.

Moderated by William J. Simmons | with Judith Brodsky, Carrie Moyer, Komal Shah, and Lisa Wainwright.

Held in conjunction with the exhibition Miriam Schapiro: The André Emmerich Years Paintings from 1957–76

The Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) admits 13 new members: The New York organization will bring on Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, Canada Gallery, Eric Firestone Gallery, Gitterman Gallery, Mignoni, Ortuzar Projects, Perrotin, RYAN LEE Gallery, and Skoto Gallery. West Coast dealers joining the organization this year include Catharine Clark Gallery, Anat Ebgi Gallery, Parker Gallery, and Paulson Fontaine Press.

Moderated by Elissa Auther | with Joyce Kozloff, Melissa Meyer, Beau R. Ott, and Mira Schor.

Held in conjunction with the exhibition Miriam Schapiro: The André Emmerich Years Paintings from 1957–76

Abigail DeVille’s exhibition, appropriately titled Bronx Heavens, begins by offering visitors an invitation to board Lunar Capsule (all works cited, 2022). The quirky Mork & Mindy–style spacecraft, with its gilded interior and Rococoesque chair—an item of furniture that conjures an elder’s sitting room, where family history is often passed down—has traveled to many cultural events and festivals, collecting stories from people of all ages that have now become treasured records of daily life on Earth.

A voice-activated microphone within Lunar Capsule captures our narratives, which are eventually broadcast through a media player connected to the headphones of a separate work, Black Monolith, a telephone booth–like object that glows with numinous blue and purple lights. A direct refutation of the idea of a singular experience of Blackness, Monolith operates like an inverse of Adrian Piper’s What It’s Like, What It Is #3, 1991, a rectangular white cube containing a series of videos in which a Black man plainly states, among other things, that he is “not shiftless,” “not childish,” and “not evil” in order to challenge any stereotypical ideas a white and presumably liberal museum-going audience might have about Black people.

In Martha Edelheit’s groovy scenes of erotic languor—featuring nudes in unselfconscious poses with intent or with distant facial expressions, usually basking in the sun—the pulsing undercurrent of optimism is most seductive. That, and the THC-Technicolor extravagance of her realist style. The ninety-one-year-old artist’s exhibition here, Naked City, Paintings from 1965–1980 which included several monumentally scaled works, spanned a period of social upheaval, when the artist labored with visionary feminist vigor. She rendered slack dicks and unidealized bodies in detail, holding the sexual revolution to its word in the realm of painting.

Presented by K11 MUSEA and K11 Art Foundation, City As Studio, China’s first major exhibition of graffiti and street art, will showcase the breadth and depth of the graffiti and street art scene across generations, styles and geographies.

Featuring over 100 works by more than 30 artists, City As Studio traces the global history of graffiti and street art from its emergence in the subway yards and parking lots of 1970s New York to its rise as a worldwide phenomenon. It begins with the movement’s pivotal innovators such as Fab 5 Freddy, FUTURA and Jean-Michel Basquiat who were part of the dialogue and the Downtown art scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s, and goes on to highlight artists such as Barry McGee, Mister Cartoon and OSGEMEOS, and the groundbreaking styles they created in San Francisco, East Los Angeles and São Paulo. The exhibition also documents the emergence and evolution of artists such as KAWS and AIKO who represent a younger generation of New York street artists.

[Edelheit’s] figures achieve true transcendence in the real space of the city. . . . The frisson of a rippling deltoid foregrounding the unloveliness of crumbling infrastructure, as in “Major Deegan Expressway With Fruit” (1972-73), both sends up Western traditions and refreshes them.

For Edelheit, the city’s built environment is as spiritually revelatory as any desert. Bodies rendered in creamy pastels merge into a single mass before the seal enclosure, or dissolve into Central Park’s lake, becoming the landscape itself, a poetic depiction of art’s fundamental indispensability from life.

Judy Bowman: Gratiot Griot

MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART DETROIT (MOCAD)

October 29, 2022–March 26, 2023

In her debut solo museum exhibition, “Gratiot Griot,” seventy-year-old mixed-media collage artist Judy Bowman pays tribute to the community that raised her.

Miriam Schapiro’s Idyll II (1956), in the section dedicated to performance and gesture, is undeniably brought to life by her sweeping, quivering brushstrokes, which simultaneously trace her own expressive movements and coalesce to suggest a dynamic throng of colourful figures. Three paintings by Yvonne Thomas (To the Forest, 1960; Exploration, 1954; and Transmutation, 1956) in the ‘Environment, Nature, Perception’ group demonstrate how the artist modified her palette to match the mood of her surroundings, ranging from shadowy blues and greens in the first work, to warm, hazy hues in the latter.

The wrenching, spiky and jagged forms in Martha Edelheit’s Sacrificial Portrait, and the frightening red and white gestures exploding against black in Sonia Gechtoff’s work, have all the attack and suddenness of a punch in the face. Corinne West, meanwhile, resorted to painting under the name Michael West. George (Grace) Hartigan and Lee Krasner, whose name was originally Lena, also felt it necessary to disguise their gender. It is no wonder women get angry.

"Too Much Is Just Right: The Legacy of Pattern and Decoration" features more than 70 artworks in an array of media from both the original time frame of the Pattern and Decoration movement, as well as contemporary artworks created between 1985 and the present.

The Addison Gallery of American Art at the Phillips Academy, Andover, MA

Comprised almost entirely of works from the collection—including Jeanne Reynal's Servants of the Sun, 1950—this exhibition explores how women have deployed the visual language and universal formal concerns of abstraction—color, line, form, shape, contrast, pattern, and texture—to create works of art across a wide variety of media (including paintings, sculptures, drawings, photographs, ceramics, textiles) from the 18th century to the present day.

Your list of must-see, fun, insightful, and very New York art events this month, including Ed Ruscha, Nina Katchadourian, Luis Camnitzer, Martha Edelheit, and more.

I am rooting for Martie Edelheit.

At the age of 91, she’s finally emerging from years of obscurity. Her mind is clear and her body agile enough to enjoy every small step of it all—a bustling opening, a post-opening dinner at the fashionable restaurant Il Buco—while leaning on a cane, or a friend’s arm. Small, fierce, outspoken, Martha Edelheit keeps pushing forward, with new 11-foot paintings and a planned return to New York City, her hometown.

I first encountered Edelheit in the context of another story, which explored the asymmetry of market acclaim for female artists based on the findings of the Burns Halperin Report.

As I wrote in December: “The overwhelming majority of women, especially women of a certain age, are ghosts as far as auction sales go. The reasons for this vary, from the market’s preference for painting over conceptual and performance art to lack of access to the gallery system to individual choices to slow artistic production during child-rearing years.”

A pioneer in graffiti, Futura needs little introduction. The artist has blazed a trail in the world of art that is as colourful as the stunning art pieces he has produced throughout his career. Born in the mid-50s in New York, Futura (born Leonard Hilton McGurr), was one of the earlier pioneers of the graffiti movement.

The Houston Museum of African American Culture presents Ellsworth Ausby: Odyssey, a posthumous exhibition of paintings by the artist Ellsworth Ausby who died in Brooklyn in 2011. The HMAAC exhibition primarily focuses on the Afrofuturist abstract painter's work on cut canvas from the 1970s which embodies his vibrant geometric forms that reflect his achievement of liberating the canvas from rigid structures, allowing them to float freely on the walls and spaces they occupy.

Spirit in the Land is a contemporary art exhibition that examines today’s urgent ecological concerns from a cultural perspective, demonstrating how intricately our identities and natural environments are intertwined. Through their artwork, thirty artists show us how rooted in the earth our most cherished cultural traditions are, how our relationship to land and water shapes us as individuals and communities. The works reflect the restorative potential of our connection to nature and exemplify how essential both biodiversity and cultural diversity are to our survival.

In 1972, the year that art historian Cindy Nemser cofounded the Feminist Art Journal, she fired off a letter to the New York Times, taking critic James Mellow to task for labeling a female artist’s exhibition a “one-man show.” “Evidently,” she wrote, “Mellow still has not caught on to the fact that women are not ashamed of their sex and resent being mistaken for men.” After protesting the reviewer’s chauvinistic language—the work was “seductive,” “feminine,” even “en déshabillé”—Nemser closed with a scorcher: “Sexist critics take note. When you start seeing scantily clad females in every abstract painting, they may start calling you ‘a dirty old man.’”

The artist in question was Nina Yankowitz, and the show was her second solo at Kornblee Gallery in New York. This past autumn, some of the same paintings were back on public view in “Can Women Have One-Man Shows?” at Eric Firestone’s two-floor space on Great Jones Street. By alluding to Nemser’s letter so directly, the exhibition not only positioned Yankowitz as a significant figure in feminist art, but also raised the issue of her early work’s reception—or lack thereof.

Are we finally back to our normal selves after almost three years of a global pandemic that upended so many lives? It’s still hard to tell, isn’t it? In most of the world, art museums and galleries sprung back to life in 2022, matching or coming close to pre-pandemic levels of programming and attendance. Here in New York, we’ve returned to the familiar pickle of too many shows running at once, and not enough time to see them all. This year, we’re going big with a list of 50 memorable shows from around the world, seen and loved by our team of editors and contributors. It’s by no means an exhaustive list, as travel was still limited this year. Instead, this is a snapshot of who we were and what we saw in 2022, including some surprises. —Hakim Bishara, Senior Editor

The auction market for Pablo Picasso is larger than that for all female artists over the past 14 years.

Peter Williams's paintings have a quality that I'd describe (without value judgment as) as "too-muchness." His works are loud, with arrays of colors in grids, stripes or dots; they feature cartoonish figures in dreamlike states, amid such symbolic imagery as basketballs, African masks, Mickey Mouse ears and flowers. Each painting is a puzzle so jam-packed with feelings and ideas, I can't help but be dazzled by it.

With reproductive rights severely under attack in the U.S., and women’s bodies yet again a battleground, feminist artist Miriam Schapiro’s groundbreaking work becomes urgently relevant, again.

By the late 1960s, the women’s liberation movement was gaining traction throughout the United States, giving rise to the women’s health movement at the end of the decade. At the moment when activists urged women to take control of their reproductive health—often beginning with handheld mirrors, flashlights, and speculums—women’s art of the period similarly focused on the female reproductive system.

Toward the end of the 1960s and into the early ’70s, Nina Yankowitz was engaged with core questions about the nature of painting. Then an undergraduate student at New York’s School of Visual Arts—at a time when two- and three-dimensional objects inhabited distinctly separate realms—she voiced a seditious desire to upend the binary: “I want to do both,” she told the head of SVA, according to her 2018 oral history interview for the Archives of American Art. In 1969, at age twenty-three, she had her first full-scale solo show at Manhattan’s Kornblee Gallery (during a period when gallery representation for women was exceedingly rare), where she showed her series of “Draped Paintings,” 1967–72, ten of which were on view in her exhibition here. Freed from the stretcher and large in scale (two of them are more than ten feet high), the reconfigured works were imposing but not overpowering. Using sailboat canvas as her ground, she engaged both surface and space with a playful spirit of experimentation. She applied spray paint with varying degrees of saturation to make colorful abstractions; she then attached the works to the wall with staples, arranging them to accentuate their voluminous folds. In their most elegant iterations, such as the sunrise-hued Goldie Lox, 1968, which modulates from a sparingly pigmented left edge to a warmly saturated right, they married subtleties of color and form. Two pieces from Yankowitz’s series of “Pleated Paintings,” 1970–72, also on view here, showed yet another way in which she pushed her experiments with three-dimensional form, adopting highly textured commercial pleating as an additional compositional tool. Pleated Diptych, 1972, revealed the complex compositions made possible by the combination of the folded substrate and spray, although its overall impact seemed more constrained than in the draped paintings.

I use color and an outsider’s point of reference in my paint handling, creating an immediacy and a response that endows the work with a sense or feel of currency. … While it is painful, for some, that I bring a state of offensive literature, I think we are also deserving of a critique by looking at representations of race and representation. — Peter Williams

Moderated by curator and critic Larry Ossei-Mensah, this panel discussion meditates on the legacy of Peter Williams (1952–2021) whose punk-pop paintings such as My Culture is Yer Freight (2019) evoke the complex experiences of Black Americans in the contemporary age. Organized in conjunction with Peter Williams: Nyack on view at Eric Firestone Gallery, this program brings together artist Dominic Chambers; artist Jameson Green; curator and gallerist Ebony L. Haynes; and poet and critic John Yau.

This panel discussion at 40 Great Jones Street will be followed by a reception at 4 Great Jones Street in the concurrent solo show Abigail DeVille: Original Night, also on view through December 23, 2022.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) announces Gratiot Griot, the first solo museum exhibition of mixed media collage artist Judy Bowman. This exhibition will present new works alongside older collages by the artist that invite viewers to engage with the rich cultural tapestry of life across the African diaspora. Gratiot Griot will be on view at MOCAD from October 29, 2022 – March 25, 2023.

Born and raised in Detroit’s legendary Black Bottom neighborhood, just off of the iconic Gratiot Avenue, Bowman creates visual works inspired by stories of African American life. Collaged images depict and highlight the intimate landscape of neighborhoods, homes and gathering places – the iconic Belle Isle, cozy and colorful living rooms and popular street corners filled with small local businesses – that encouraged Bowman’s development as a griot. In West African tradition, a griot is a storyteller who, through creative performance, preserves and shares the cultural legacy and histories of their people. Gratiot Griot highlights Bowman’s extensive career as a storyteller.

In the spring of 1963, the New York Art Committee for Tougaloo College established Mississippi’s first collection of modern art at Tougaloo, a historically Black college located north of Jackson. As civil rights protests swirled across the fiercely segregated state, the College became an unlikely hub of European and New York School modernism and a place that the collection’s founders envisioned as “an interracial oasis in which the fine arts are the focus and magnet.” Co-organized by the American Federation of Arts and Tougaloo College, Art and Activism traces the birth and development of this significant and distinctive collection. With approximately thirty-five artworks by artists such as Francis Picabia, Jacob Lawrence, and Alma Thomas, the exhibition brings renewed attention to a complex American collection established at the intersections of modern art and social justice.

"A highlight was the celebration of some of the female (abstract) greats—Joan Mitchell (Helly Nahmad), Helen Frankthaller (Berggruen Gallery) and Pat Passlof (Eric Firestone Gallery) and Vivian Springford (Almine Rech)."

The buzz of contemporary art at Frieze London might take centerstage in October, when the U.K. city’s art galleries bring out their finest works, but the fair’s classic arm Frieze Masters is where the hidden gems are.

Featuring more than 120 galleries, Frieze Masters is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year as well as its recent debut in Seoul. The fair’s main section has around 97 galleries from around the world presenting works spanning six millennia of history (in organizers’s words), from ancient artifacts to Modern art, as well as previously unrecognized talent.

The main exhibitors are joined by 28 galleries in the Spotlight section dedicated to women artists curated by Camille Morineau, co-founder and research director of Archives of Women Artists, Research, and Exhibitions (AWARE), and her team. And Luke Syson, the director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, is the curator of the Stand Out section, highlighting 10 galleries under the theme of global exchange.

Our highlights of the art historical (re)discoveries in this year’s Frieze Masters center around female artists from a diverse cultural and geographical background. Many of them have lived through turmoil and upheavals of the 20th century, or having struggled to find a foothold in a male-dominated art world. Eventually they succeeded in creating these rich bodies of work that helped to push the boundary

Curator Alexandra Schwartz, who recently organized Garmenting: Costume as Contemporary Art (2022) at the Museum of Arts and Design, will moderate a conversation with Nina Yankowitz, Joyce Kozloff, and Meg Lipke regarding their daring approaches to abstract painting. This discussion will consider how each artist has moved beyond painting’s traditional form. Often leaving behind the conventional stretched canvas support, these practitioners have embraced handicraft techniques or alternative materials while intervening in space in novel ways.

This program is organized in conjunction with Yankowitz’s solo exhibition of unstretched paintings from the 1960s and ‘70s at Eric Firestone Gallery.

To register for the Zoom link, visit the link below:

REINVENTING ABSTRACT PAINTING | A PANEL DISCUSSION AT ERIC FIRESTONE GALLERY

In a body of work that drapes over the edge what was and what will be, Futura2000’s Tarpestries summon up the memory of a grittier (and perhaps more exciting) New York City subway as much as they do your favourite scenes from Dr. Who and Blade Runner. There are than 20 of these upstretched “tapestries” on view, which range from seven to 25 feet, at Eric Firestone’s two locations in East Hampton. The monumental size gives viewers the chance to see Futura2000’s work in its natural form: large scale, enveloping, as if it was once part of the city. The tapestries is juxtaposed with a massive bronze sculpture of “39 Meg", the robotic visitor from another planet that has beamed its way into the artist’s work on more than one occasion.

After thirteen years and twenty-one exhibitions, rennie museum announces our final presentation in the historic Wing Sang building. The exhibition opens August 13 and concludes November 12, 2022.

Featuring fifty-one artworks by thirty-seven prominent artists from A(bdessemed) to Y(iadom-Boakye), the farewell exhibition breaks the museum’s self-imposed rule of not titling its shows. 51 @ 51 references the number of artworks in the exhibit as well as the address of the museum—51 East Pender Street.

When Shirley Gorelick was in high school in the late 1930s, she took art classes on weekends and in the summers from the sculptor Chaim Gross and painters Moses and Raphael Soyer at the Education Alliance in New York City. Still early in the search for her own visual style, she was already quietly rebellious. She recalled in 1968 that “the painting class didn’t interest me. It was too crowded and I couldn’t see. And I felt I had to be right up front to see.” But Gorelick did pursue painting, landing in the late 1960s as a masterful painter of large-scale, realist figures. In these portraits, which she made through the early 1980s, that imperative to be right up front takes the form of a close attention to her subjects and the exchange that occurs between them and the viewer. Larger than life-size, the figures crowd into our space, so near that sometimes their bodies are truncated by the edges of the canvas.

“Family,” a new exhibition curated by Max Warsh at Eric Firestone Gallery in New York, gives an overdue look at Gorelick’s intimate and psychologically penetrating portraits of the five families who mattered most to her. These were people who did not then typically find themselves the subjects of art: middle-aged women, disabled people, mixed-race families, and older couples. David Ourlicht, one of Gorelick’s subjects and the son of Libby Dickerson, the model to whom Gorelick returned most often, said of his mother’s involvement, “The personal relationship came first.” The two women shared progressive politics, he said. “It was equal rights, women’s rights, gay rights, civil rights.”

Water, Water

"Holy Water," an exhibition of work by more than 20 contemporary artists from around the world, will open at Eric Firestone Gallery's Garage, 62 Newtown Lane in East Hampton, with a reception Saturday from 6 to 9 p.m. It will continue through July 24. The artists were invited to create works responding to the theme of water. Fishing and surfing, baptism and migration, ordinary marine life and fantastical sea gods and monsters are among the subjects.

"Collage/Assemblage," on view through Aug. 6 at Eric Firestone Gallery in East Hampton, juxtaposes the work of historic and contemporary artists who use collage and assemblage in their practices. Among them are Shinique Smith and Emmanuel Massillon, whose work explores issues of identity and hybridity; Joe Overstreet, who collages strips of acrylic paint over his stretched canvases; James Phillips, whose compositions reflect his association with AfriCOBRA, a Chicago-based group of African-American artists, and Varnette Honeywood, Judy Bowman, and Derrick Adams, whose collage works celebrate Black culture.

Larger-than-life terracotta heads form an operatic visual finale in Eric Firestone Gallery’s exhibition Reuben Kadish: Earth Mothers. An amalgam of human beings and some strange subspecies, these crenellated heads, which look as if they were built from jagged scree, radiate a silent nobility. Frozen in semi-repose or grim rumination, or perhaps caught in death throes, they loom like beatific elders from a civilization wiped out by divine ordination, or by some cosmic whim.

In fact, confronting the unimaginably real, and responding to premonitions of cataclysm and its aftermath, inform sculptor Reuben Kadish’s art as well as his biography. Born in Chicago in 1913 and raised in Los Angeles, he attended high school with Jackson Pollock, a lifelong friend, and furthered his studies at Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) in 1930 before apprenticing under Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Amid the political despair of the mid-1930s, he traveled to Morelia in Mexico and, collaborating with Philip Guston, created a 1,000-foot mural, “The Struggle Against War and Fascism” (1934–35) — a nightmarish epic that rang alarms about global far-right political terror and its concomitant militaristic barbarisms.

But the mural project was only the first act in Kadish’s artistic interventions based on humanity’s universal inhumanity. During World War II, while in the US Army Artist Unit, he was commissioned to photograph civilian carnage in Burma and India, savageries that he further memorialized in pen-and-ink sketches. These acts of witness presumably gave rise to the artist’s poignant, sublimated ethics of paying close, empathic attention to corporeal anguish.

The abundance of artwork in Earth Mothers, along with the works’ varied scale and psychological tenor, make sculpture seem like Kadish’s destiny from day one. But he only committed to it in full after a studio fire in the late 1940s destroyed most of his paintings. The surviving canvases — many done in what came to be known as an Abstract Expressionist mode — are featured here and underscore how, in turning from purely abstract painting to imaginative and figurative sculpture, he found a far more suitable métier for cultivating and refining an existential outlook.

Partly instigated by the archeological fieldwork of his wife, Barbara Weeks, who introduced him to ancient sculptures from far-flung times and epochs, especially from the Kingdom of Benin and the Aztec Empire, Kadish tirelessly produced one sculptural series after another until his death in 1992.

It started with an exhibition catalog from the 1970s—one with eerily contemporary work and the names of two largely overlooked female artists, Eva Hesse and Nina Yankowitz. Both had been rightfully featured in the 1970 Emily Lowe Gallery exhibition in Hempstead, New York, but their work had been victimized by systematic failure. Female artists in the 1970s—especially those finding creative inspiration outside of New York City—rarely found a market foothold and, to Eric Firestone, needed a proper reintroduction for today’s audiences. For Firestone, the catalog was a catalyst and a moral obligation to reignite dialogue around Yankowitz and Hesse, and present them amongst their peers in the gallery's current show, "Hanging/Leaning: Women Artists on Long Island, the 1960s-80s." Firestone was sold when Yankowitz pulled out Sagging Spiro (1969) from her "Draped Painting" series of linen panels. “They feel so relevant and fresh and in dialogue with multiple artists,” says Firestone. “Once people know about this work. I think it's going to be a revelation.” The mixed media piece, which hangs front and center of Firestone’s Newton Lane outpost in East Hampton, sings with the same harmony as Sam Gilliam and Katherine Grosse, though Sagging Spiro predated the artists by three and 30 odd years, respectively. The work is a perfect introduction for the mixed-media exhibition, which plays with Long Island’s geographic surroundings, the beat-poet vibe of the '60s- and '70s-era Hamptons and general energetic joy in the unsung.

Mostly New: Selections from the NYU Art Collection presents modern and contemporary artworks, the majority of which have entered the New York University Art Collection over the last decade.

The founding of the NYU Art Collection followed A. E. Gallatin’s Gallery (later, Museum) of Living Art, which operated from 1927 until 1942 in the same space the Grey currently occupies. As the first American institution to exhibit living artists, Gallatin’s Museum provided an important forum for contemporary visual expression and access to original works for NYU students. Initiated in 1958, the NYU Art Collection grew quickly through the mid-1960s, with many sculptures, drawings, prints, and photographs installed throughout the campus. In 1975 Abby Weed Grey donated some 700 works from the Middle East and Asia dating primarily from the 1960s—a magnanimous contribution that also established the Grey Art Gallery as NYU’s fine arts museum. The collection will again expand significantly with Dr. James Cottrell and Joseph Lovett’s promised gift of approximately 200 artworks—a number of which are on view here—by downtown New York artists.

The project was born of necessity. When Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro began the Feminist Art Program at CalArts, the school’s new Valencia campus was not complete, so they had to work off-site. They decided to use a soon-to-be-demolished 17-room house in Hollywood with broken windows, no plumbing and no heat as their studios and exhibition hall. Students worked together for weeks clearing rubbish, replacing and glazing windows and painting walls, while also developing their art and their confidence as artists. With group sessions that Chicago calls content-searching and others call consciousness-raising, the programme was so physically and psychologically demanding that alumnus Mira Schor compares it to boot camp. “It was very intense—unlike anything I had ever experienced before,” she says, “and I made sure never to experience exactly that again.”

Organised by Anat Ebgi gallery called Womanhouse 1972/2022 (18 February-2 April) exploring the Feminist Art Program, its origins and its legacy.

Pat Passlof

ERIC FIRESTONE GALLERY | NEW YORK

Pat Passlof (1928–2011) was an important figure in the development of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism. She was there from the beginning and, indeed, one of its incubators. In 1948, she studied with Willem de Kooning at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, the place to be if one wanted to become an avant-garde artist. That was also the year Arshile Gorky committed suicide; his Surrealized take on abstraction, along with that of his friend de Kooning, remained an influence on Passlof. But as “Memories of Tenth Street: Paintings by Pat Passlof, 1948–63”—a presentation at Eric Firestone Gallery that featured a thoughtful selection of works the artist created in Manhattan’s East Village at the titular address—made abidingly clear, Passlof’s painterly innovations eschewed the aggressive grandiosity of her mentors for something more lyrical, intimate, and inviting. Even though Untitled, 1950, with its thin black lines and planar, smeary sections of pale gold and white, seems indebted to Gorky’s paintings, and Theater, 1957, with its turbulent facture and thick encrustations of dirty violet, red, and fawn, carry a generous dose of de Kooning’s method, Passlof truly astonishes in such delicate, subtle works as Miss Julia, 1961, with its quivering, luminescent surface awash in sundry pinks, yellows, browns, and blues radiating from a loosened grid. In this “pure” abstraction, Passlof achieves aesthetic independence. “The being of the work of art yields itself only through its sensuous presence,” French phenomenologist Mikel Dufrenne wrote, “which allows [us] to apprehend it as an aesthetic object.” Outgrowing the lessons of her confreres, Passlof comes into her own with extraordinary sensuousness. It seems safe to say that without Black Mountain College there would have been little or no future for avant-garde art. (And Europe, where it had developed, had become a war-torn ruin by 1948.) It is important to emphasize the year Passlof began studying with de Kooning: The New World was the place to revivify the sensation of the new, which had become timeworn and stale in the Old World. It also seems safe to say that Passlof’s transcendental aesthetic, and its subliminal affinity with American Luminism, surpasses the more earthbound—dare one say heavy-handed?—work of de Kooning and Gorky.

Passlof was instrumental in the restoration of vanguard culture in more ways than one. As the gallery’s press release tells us: “In 1949, Passlof helped renovate the Eighth Street loft, which was the first location of ‘The (Artists’) Club,’ attending every talk and panel. Noticing that many of her peers rarely spoke when they came to the Club, she decided to organize an alternative ‘Wednesday Night Club,’ envisioning it as a kind of ‘junior club.’ The Wednesday evening sessions quickly became popular, leading the old guard to squelch it for fear of competition.” Clearly, Passlof was in the thick of it, fearlessly holding her own despite the condescending dismissal of her paintings as retardataire—“more ‘impressionistic’ than ‘abstract,’” as Donald Judd once wrote, along with his trivialization of her color as “somewhat sweet,” another coyly misogynist characterization. Certainly Passlof’s paintings don’t climb the wall like desperate, erect penises the way Judd’s sculptures do, the boxes that constitute them a record of so many feckless orgasms. If the Abstract Expressionists were masturbators of gesture, then Judd was a masturbator of geometry. These were so-called big men: They always seemed to live in fear of the “junior club,” i.e., smart, pioneering women.

— Donald Kuspit

Thomas Sills (1914-2000) is, for many contemporary viewers, a discovery: Much of the work in “Variegations, Paintings From the 1950s-70s” at Eric Firestone was in storage before being mounted here. Sills was hardly unknown during his lifetime, though. He socialized with New York School painters like Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko and had several solo exhibitions at the historically significant Betty Parsons Gallery before receding from the art world around 1980.

Sills’s paintings here include many of the traditional mid-20th-century New York School concerns. Abstract canvases with colored interlocking forms like “Travel” (1958) and “Son Bright” (1975) have a vibrant, dynamic tension similar to works by Lee Krasner and Piet Mondrian, who played with the painterly grid, and with the fleshy, promiscuous pink favored by de Kooning. Sills’s surfaces are also notable. He used rags instead of brushes to finish his paintings, and this gives the pigment a particularly even look, beautifully integrated into the canvas surface.

Unbound brings together a multigenerational group of artists whose work takes an inventive and experimental approach to abstraction.

The MFAH presents the U.S. tour of Afro-Atlantic Histories, an unprecedented exhibition that explores the history and legacy of the transatlantic slave trade. The exhibition comprises more than 130 works of art and documents made in Africa, the Americas, the Caribbean, and Europe across 500 years, from the 17th century to the 21st century.

Afro-Atlantic Histories dynamically juxtaposes works by artists from 24 countries, representing evolving perspectives across time and geography through major paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, photographs, time-based media art, and ephemera. The range extends from historical paintings by Jean-Baptiste Debret, Frans Post, and Dirk Valkenburg to contemporary art by Melvin Edwards, Ibrahim Mahama, and Kara Walker.

The exhibition premiered at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) in Brazil, and the U.S. tour builds on the presentation through the overarching theme of histórias—a Portuguese term that can encompass both fictional and non-fictional narratives of cultural, economic, personal, or political character. The term is plural, diverse, and inclusive, offering viewpoints that have been marginalized or forgotten. Afro-Atlantic Histories unfolds through six thematic sections that explore the varied histories of the diaspora.

On the busy thoroughfare of Grand Concourse in the south Bronx stands a contemporary building resembling origami folds. Home to the Bronx Museum of the Arts, this cultural institution offers the Bronx and greater New York City seasonal exhibitions and an impressive permanent art collection. Currently on display is Henry Chalfant’s graffiti archive and Alvin Baltrop’s queer photography. The museum relies on donations and grants to guarantee free entry to all visitors, so a celebratory fundraiser dinner was a natural fit. 2019 marked the museum’s inaugural BxMA Ball, a multi-sensory gala co-chaired by Angel Otero and Jerome Lamaar.

Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019 foregrounds how visual artists have explored the materials, methods, and strategies of craft over the past seven decades. Some expand techniques with long histories, such as weaving, sewing, or pottery, while others experiment with textiles, thread, clay, beads, and glass, among other mediums. The traces of the artists’ hands-on engagement with their materials invite viewers to imagine how it might feel to make each work.

Joe Overstreet’s 1972 unstretched, untitled canvas unfurls from the wall in a similar fashion to Eric N. Mack’s “Pelle Pelle” (2017), which is made with a microfiber blanket, polyester fabric and silk curtains tacked to the wall. Paintings and assemblages from the ’70s based on the grid by Joan Snyder, Howardena Pindell, Sean Scully and Al Loving sit comfortably next to more recent riffs on geometry by Sadie Benning, Matt Connors and Dona Nelson.

Titled “Double Portrait,” this electrifying exhibition unites Mimi Gross and Marcia Marcus, who began making figurative paintings in the 1950s. Born 12 years apart, Ms. Marcus and Ms. Gross crossed paths in downtown New York, as well as on sojourns to Italy and Provincetown. Both were putting paint to canvas at a time when Minimalism and Conceptualism reigned supreme, and both were interested in representations of their gender.