Eric Firestone Gallery is pleased to announce Hanging / Leaning: Women Artists on Long Island, 1960s–80s. Opening in East Hampton on Memorial Day Weekend, this sweeping exhibition celebrates the formal ingenuity of postwar women artists with connections to the region. Featured artists include:

Lynda Benglis, Nanette Carter, Seena Donneson, Mary Grigoriadis,

Sheila Isham, Valerie Jaudon, Joyce Kozloff, Li-lan, Pat Lipsky,

Adrienne Mim, Patsy Norvell, Beverly Pepper, Howardena Pindell,

Dorothea Rockburne, Miriam Schapiro, Joan Semmel,

Carolee Schneeman, Arlene Slavin, Michelle Stuart,

Kay WalkingStick, Nina Yankowitz, Barbara Zucker

In the 1960s through ‘80s, these artists established studios, spent time, or exhibited on Long Island. There, they sought to expand the abstract mode with new techniques, materials, and perspectives. The East End—with its social circles, coastal surroundings, and exhibition opportunities—framed or even influenced their daring experiments with form.

Teeming with highly original works, Hanging / Leaning: Women Artists on Long Island, 1960s–80s revisits this rich history of making and presenting art. The exhibition carries on Eric Firestone Gallery’s interest in reexamining the postwar scene on Long Island, underscoring the role of female abstract artists. Hanging / Leaning will unfold across the gallery’s spaces in East Hampton: its primary location at 4 Newtown Lane; and its 7,000 square-foot warehouse at 62 Newtown Lane, opening to the public for the first time.

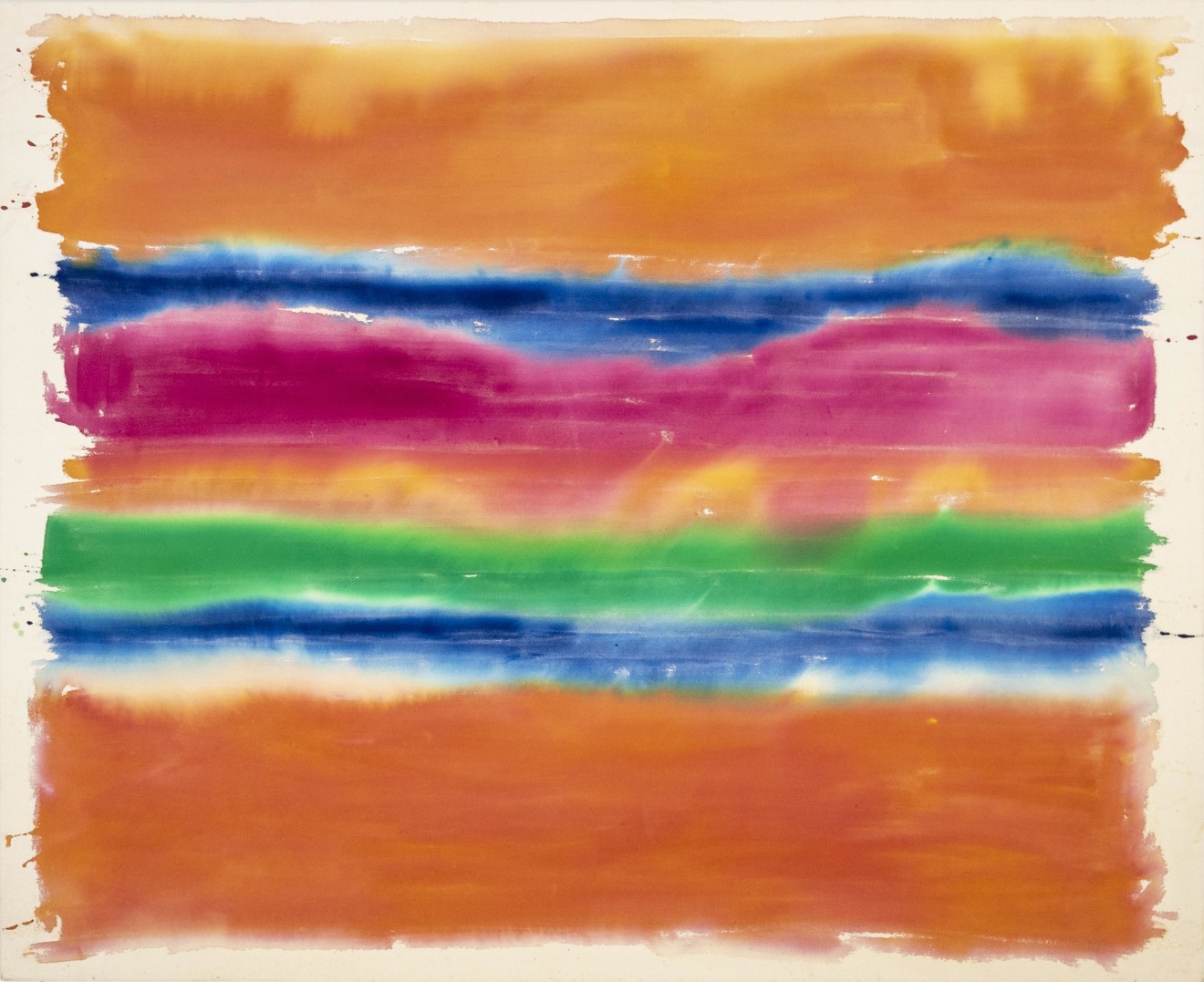

This exhibition riffs on a show organized on Long Island half a century ago. On view in 1970 at the Emily Lowe Gallery at Hofstra University in Hempstead, Hanging / Leaning presented objects that go against the orientation and composition of traditional painting. It featured twelve artists—two of whom were women, Eva Hesse and Nina Yankowitz. Leaving behind painting’s drum-taut support, Yankowitz contributed Sagging Spiro (1969) from her Draped Painting series of unstretched canvases that she sprayed with mists of acrylic paint, producing atmospheric expanses and bleeding bands of color, and then hung in soft folds that cascade down the wall. Alongside other early works by Yankowitz, Sagging Spiro will be on view in this upcoming exhibition that departs from the original show by investigating the achievements of postwar women abstractionists. Rather than limit its scope to certain art forms or the usual suspects, this Hanging / Leaning explores the field expansively—with shared place as its unifying principle.

Postwar Long Island was a hub of artistic activity where collectives flourished beyond the New York City scene. Miriam Schapiro, who was first invited to the Hamptons by renowned gallerist Leo Castelli, bought a house in Wainscott in 1953 that became a legendary gathering place for artists. It was there that Schapiro began cultivating her own abstract lexicon rooted in her experiences as a woman and mother. By the 1960s and ‘70s, Schapiro would produce masterpieces such as Fan of Spring (1979), an impeccably constructed and painted fabric collage in the feminine shape of a fan that linked modern painting to women’s craft. Nanette Carter also found kinship in the 1970s and ‘80s when she became affiliated with Al Loving and other Eastville Artists, a collective of mostly Black American practitioners in Sag Harbor. In Carter’s oil pastels from that period, Illumination #1 (1984) and Illumination #41 (1986), countless miniscule marks swirl within surges of organic forms that visualize sound waves.

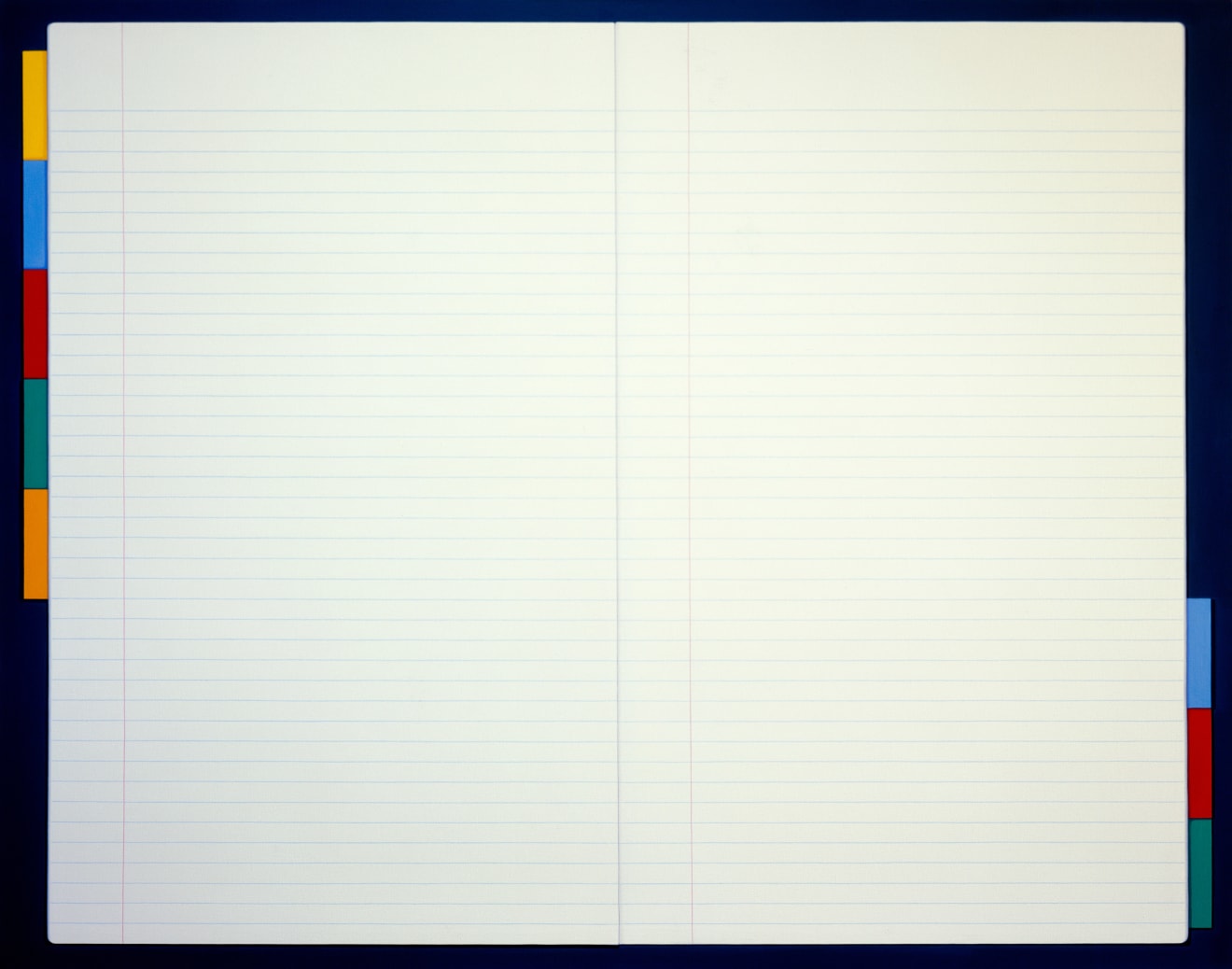

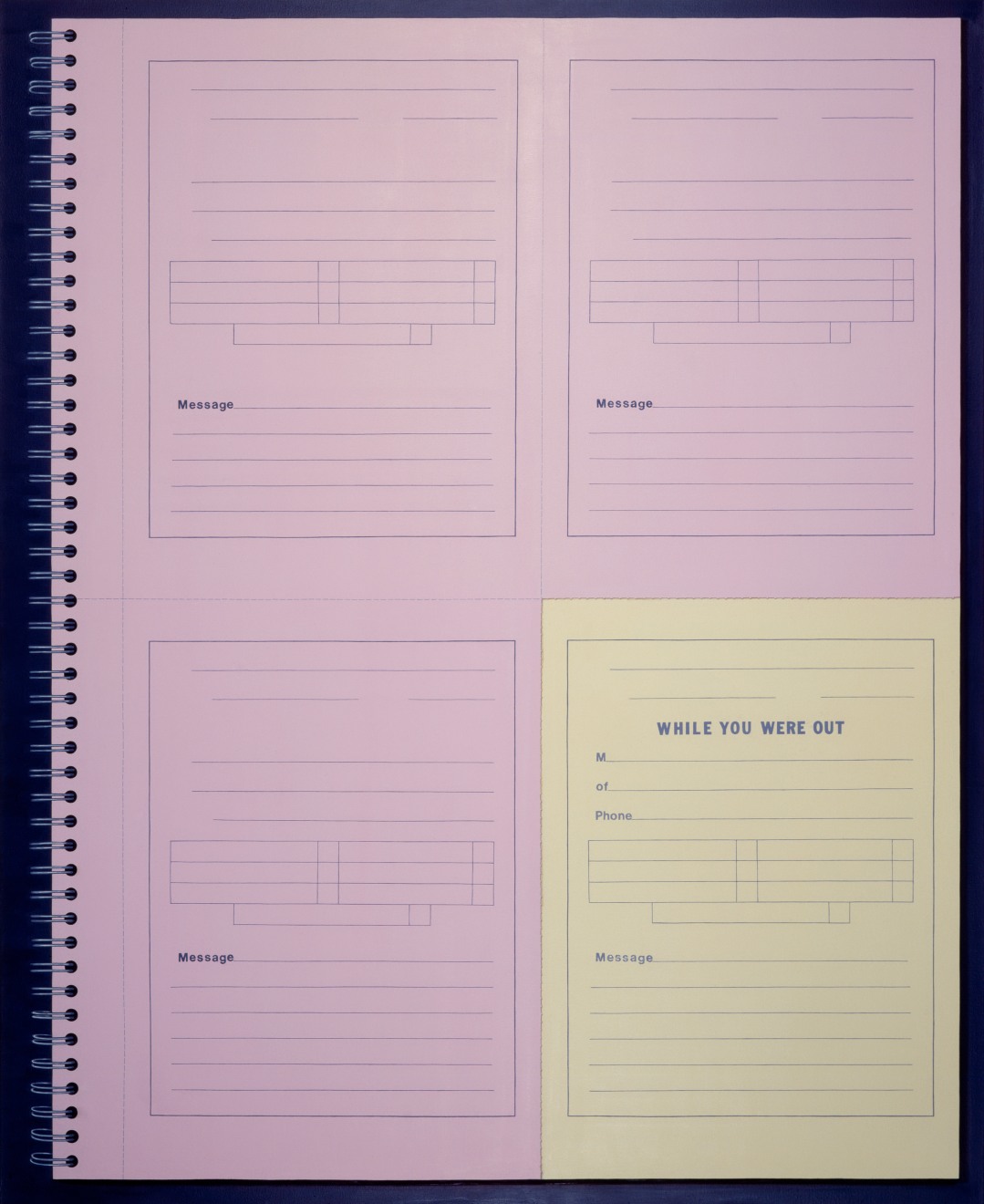

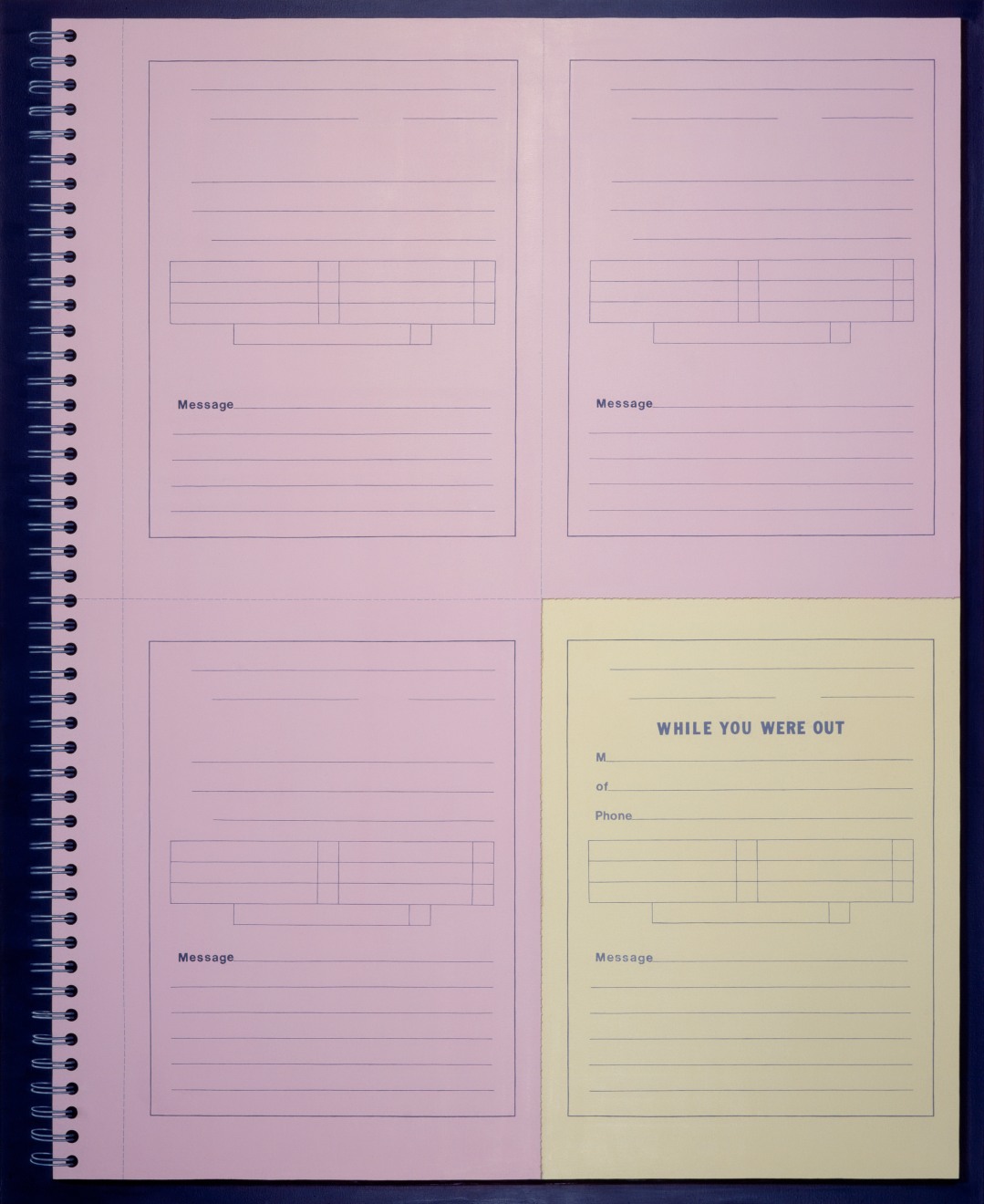

Pat Lipsky sought to engage with East End titans such as Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock by renting a house near their East Hampton residence: “I thought being that close some of the Pollock vibe might waft my way, and certainly the edges on my paintings that summer, 1969, are an adaptation of his drips.” The titles of her works often reference Long Island streets and ponds. The atmosphere also made its way into the practice of Li-lan. Li-lan expressed how the natural daylight in East Hampton influenced her output, which, until then, she produced under artificial lights in dark studios in New York City and Tokyo: “My bright city colors first turned dark, then darker; then white. The paintings became quiet and full of white light. Slowly, the white of the outside became the white of inside. White paper, pads, and notebooks that had been in the background, gradually became the foreground.” This shift is evident in Absent and Present, 1 (1979), a white expanse that reveals itself to be an open pad of paper only through the spiral binding depicted along the right edge. Similarly, Kay WalkingStick’s 1983 residency in Montauk via the Edward F. Albee Foundation was a watershed in her practice: After experiencing the area’s topography, landscape became the root of both her abstract and representational compositions.

Other artists embraced unconventional processes to capture their Hamptons environs. Sheila Isham detailed her move to the East End as one that drew her closer to nature: “I liked the feeling of earth and sea and sky. … The way the sky interacts with the earth and how the sea plays a role. It’s always there, that interplay between the three.” Combing her beachy surroundings, Isham would hold seaweed, sponges, and other substances against canvas, using an airbrush to spray acrylic around them. This approach resulted in dynamic storms of color such as Galaxy — Sun Penetrating Wind (1968). In another approach, Michelle Stuart rubs soil and other elements from sites like Long Island on paper to record marks made on the earth, producing textured and tonal archives of place as The Bridge (1975–80) exemplifies. Patsy Norvell, who by the 1970s had already been constructing intricate compositions made of hair, shifted to sand-blasted glass inspired by the freedom of space and her blossoming gardens in Southampton. Appearing as a window or doorway to a thicket of flora (recalling the lattice archway in the artist’s backyard on Long Island), Lady in Waiting (1982) is one such monumental painted glass piece that Norvell conceived with her then-husband, Robert Zakanitch. Both Norvell and Stuart presented similar works in Reflections: New Conceptions of Nature (1984) at the Hillwood Art Gallery at Long Island University in Greenvale.

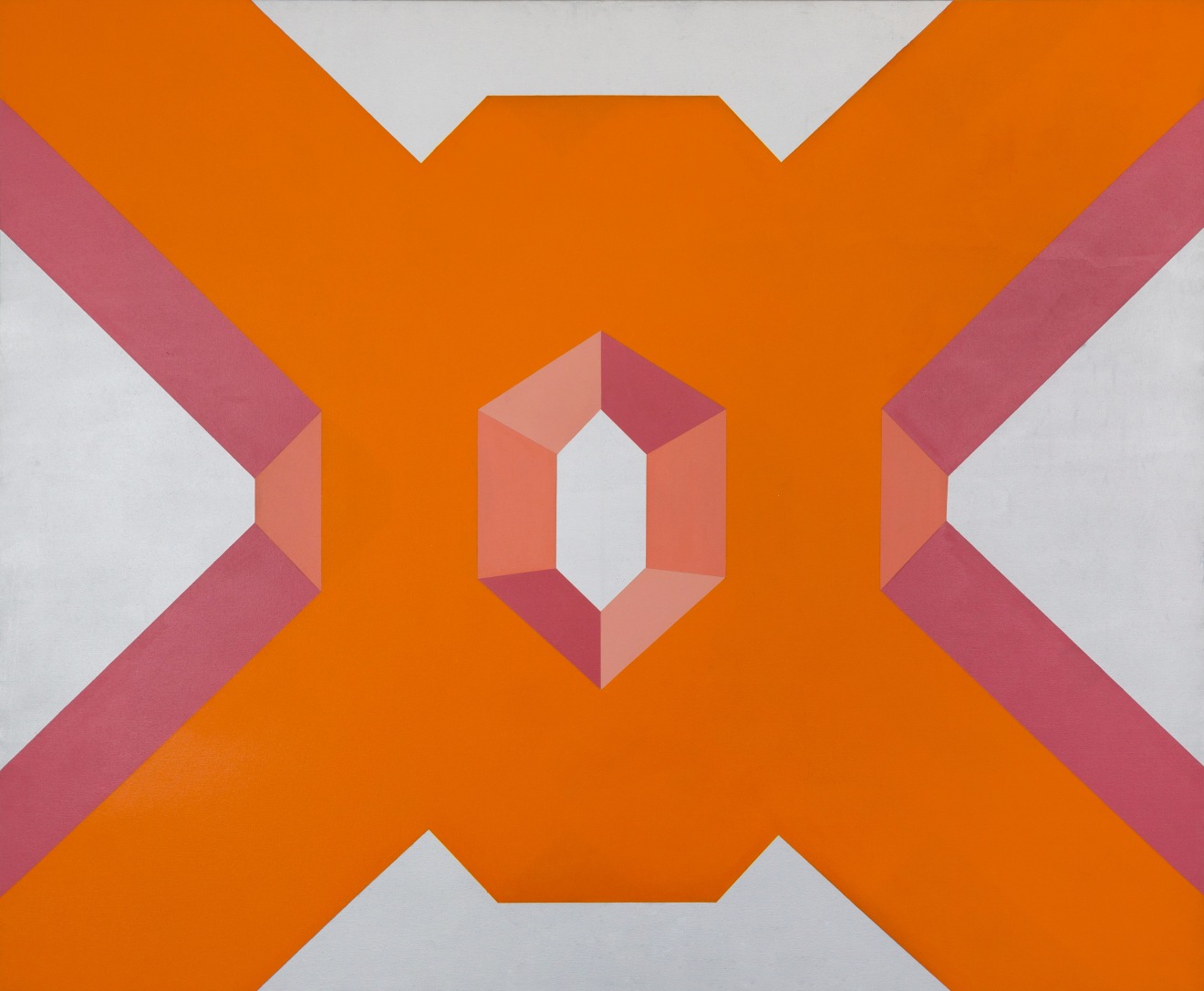

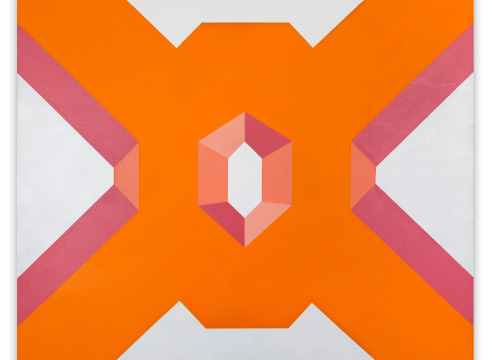

While Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism were waning in New York City in the late 20th century, the Hillwood Art Gallery was among many organizations on Long Island that gave women space to showcase their evolving formal aesthetics. Beverly Pepper and Barbara Zucker were featured in exhibitions at the Nassau Art Museum in Roslyn. The female-founded arts center Guild Hall in East Hampton showed Schapiro, Li-lan, Carter, Mary Grigoriadis, Sheila Isham, and Adrienne Mim; while the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill displayed Schapiro, Li-lan, and Slavin. Such institutions continued to support such artists and others like Valerie Jaudon by acquiring their early work. Although Howardena Pindell did not exhibit at such regional institutions—and vocalized how locales such as the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan and the Hamptons often excluded minority artists—she has spent a large part of her career on Long Island teaching burgeoning art students at the State University at Stony Brook.

Perhaps no organization in the area exhibited more emerging female artists than the Elaine Benson Gallery in Bridgehampton. As Elaine Benson explained, her eponymous gallery that opened in 1965 at first struggled to establish itself: “[Artists] were reluctant, because there were no galleries here, they were all in New York, and there was a theory that if you had a show out here, people would come to the party and drink your wine, but would never buy anything.” Yet by the 1980s, thanks to Benson’s prominence in the community (and her knack for event-planning), artists were knocking at her door. She went on to mount solo shows on Schapiro, Li-lan, Isham, Mim, Zucker and Seena Donneson while including Dorothea Rockburne and Arlene Slavin in surveys.

The Elaine Benson Gallery set the stage for more comprehensive presentations on Long Island of women’s art. Yankowitz, Schapiro, Lynda Benglis and Joyce Kozloff took part in Unmanly Art (1972) at the Suffolk Museum, which is cited as the first in-house museum survey of women artists. Closely following that show was Women Artists Here and Now (1975), curated by Kozloff and Joan Semmel at Ashawagh Hall in East Hampton. Featuring Schapiro, Li-lan, Benglis and Carolee Schneeman (among others), Women Artists Here and Now revealed the female artistic talent that saturated East Hampton despite its reputation as an enclave for male Abstract Expressionists. “We were in the belly of the beast,” Semmel said of women artists in the village. “We were fearful of all-women shows too. They could be the kiss of death.” Semmel and Kozloff persisted in mounting what proved to be a groundbreaking exhibition—one that staged canonical feminist works like Schneeman’s Interior Scroll performance.

While Semmel is widely known for figuration, and Schneemann for body art, both figures pursued abstraction early in their careers—a fundamental facet of their oeuvres that has been overlooked. Bright saturated colors, dense clusters of shapes, and unusual spatial dynamics define Semmel’s abstract canvases of the 1960s and ‘70s, which gradually gave way to the psychedelic palettes and surreal figure-ground relationships of her later art. By contrast, Schneeman created textured and thickly collaged paintings in the 1970s and ‘80s in tandem with her performances which she described as “extending visual principles off the canvas.” A key early Semmel is on view alongside Schneeman’s Green Line (1983). Shrouded with fabric, splashed with acrylic paint, and intersected with a green cross, Green Line does away with painting’s conventional frame and support. It also rejects the Abstract Expressionist principle that abstraction should not contain narrative content by alluding to the Lebanese Civil War.

Hanging / Leaning: Women Artists on Long Island, 1960s–80s takes a fresh look with a contemporary eye at such trailblazing historic work. In conjunction with the show, Christina Mossaides Strassfield, Director and Chief Curator of Guild Hall, will lead a panel discussion on Saturday, June 11, 5:00-6:30 PM focused on honoring and extending the legacy of Long Island cultural organizations that have supported women artists since the postwar era.