Miriam Schapiro: The André Emmerich Years, Paintings from 1957–76

Eric Firestone Gallery

40 Great Jones | New York, NY

March 22–May 13, 2023

Opening Reception: Wednesday, March 22 | 6:00–8:00 PM

Eric Firestone Gallery is pleased to announce the exhibition Miriam Schapiro: The André Emmerich Years, Paintings from 1957–76. Miriam Schapiro (1923–2015) is now well-known as a pioneer of the Women’s Art Movement, and for her contribution to the Pattern and Decoration Movement. She fused craft work, traditionally made by women, with modern painting in collages termed “femmage.” However, this exhibition will additionally shed light on her early Abstract Expressionist canvases, and her pioneering approach utilizing computer technology to create Hard Edge geometric painting in the 1960s. Spotlighting the legacy of this feminist artist, the exhibition will explore three stylistic phases, with significant examples from these two decades of Schapiro’s career.

In 1958, Schapiro became the first woman artist to have a solo show at André Emmerich Gallery. (Helen Frankenthaler was the subject of a solo show at Emmerich in 1959.) It included the monumental painting Fanfare, now in the collection of the Jewish Museum, New York, as well as the painting Nightwood, which will be shown in the current gallery exhibition. These Abstract Expressionist canvases are energetic, lively, and gestural yet also rooted in the landscape, the body and maternal experiences. Dore Ashton reviewed the exhibition in the New York Times, praising Schapiro’s “vigorous, lusty translations of sensuous experience,” but noting her tendency to “mute” color and the “blending, softening, and melting” of the paint with the surface underneath. In retrospect, this language actually reflects Schapiro’s overarching commitment to reflect femininity and the female experience. Her early abstractions were often based on figurative source material like film stills and news photographs, and explore the roles women occupy: as wives, mothers, and hopefully, agents of their own careers.

By the third solo exhibition at Emmerich in 1961, Schapiro was exploring the compositional format of a single vertical band through the center of the canvas, in which she incorporated shapes and symbols that were associated with the feminine. They included primary forms like a rectangle—which became an aperture or window, and also would develop into what she termed the “central core,” associated with a woman’s body. Along with more geometric forms, she also utilized bodily suggestive painterly gestures. Of one significant example, titled The Game, Schapiro wrote:

In 1960 I made a picture called The Game. The Game is the game of making a real world on canvas. The Game is also the game of knowing that the made world can never be wholly real. The Game was the first painting to use the box as a symbol. The box became a house. I could no longer live in the jungle. I built the house out of all things I was unsure of and certain about. I called it a “Shrine.”

Schapiro’s “Shrine” paintings of the early 1960s, which were the subject of a solo exhibition at Emmerich in 1963, eliminate the gestural in favor of illusionistically rendered, metaphysical compositions where symbols like an egg, personal items like paint tubes, or references to art historical paintings, are set within the apertures of a shrine form.

In 1967, Schapiro moved to California for her husband, painter Paul Brach, to serve as the chair of the newly formed art department faculty at the University of California San Diego. Art historian Maddy Henkin writes, “In the male-dominated department, Schapiro had no colleagues with whom she could share her growing interest in the women’s movement. As a result, Schapiro retreated into her studio until she discovered collaborators of an altogether new kind: the scientific community.”

Beginning in 1967, Schapiro used computers and custom software to create monumental hard-edged abstractions that still evoke the female form and perspective, and often reflect the landscape and architecture of Southern California. She worked with Jef Raskin, lead designer of the first Macintosh computer, and physicist David Nabilov. Henkin describes:

"Though her exact method varied over time, Schapiro always began with a simple hand-drawn shape related to vaginal iconography. The drawing would then be translated into numbers representing points on a grid that a custom computer software would rotate through space, printing out 50 views of the artist’s original drawing…Once she selected her shape, Schapiro planned the composition and then used an opaque projector to enlarge the image onto her canvas, traced the shape with a pencil, taped off the contours, and spray painted. Finally, with gusto, she removed the tape."

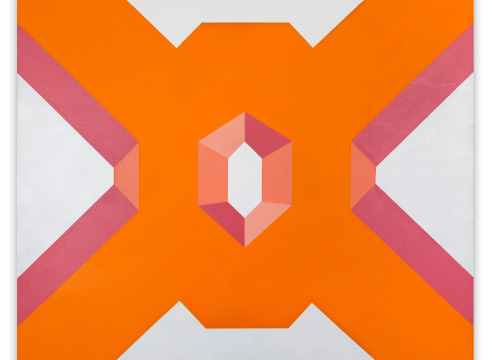

These shifts in style were clearly supported by Emmerich Gallery, where Schapiro continued to have bi-yearly shows of her hard edge work in 1967, 1969, and 1971. Her “Ox” series was exhibited in 1969. In these paintings the forms of the letters “O” and “X” are superimposed in tones of pale orange and pink, and illusionistically rendered in space to create a central aperture. Big Ox #2 is in the permanent collection of the San Diego Museum of Art, La Jolla, and currently on view. The nine-foot wide Big Ox, (1967) will be on view in this gallery exhibition. Other examples of the Ox series rotate the shape in space through various formations. Of these paintings, Schapiro reflected:

"The O was actually a hexagon with a pink labial interior, whose geometry masked its sexual meaning. In painting this image I behaved unconsciously like all women artists mentored by men. The piece was so powerful to me that when it was finished I turned it to the wall for six months before I dared approach it again." (Schapiro in The Power of Feminist Art, eds. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, New York: Abrams, 1994, 74)

Over the course of the 1970s, Schapiro became famous for various feminist collaborations. In 1971, she established the Feminist Art Program with Judy Chicago at CalArts. They partnered with their students to stage the legendary Womanhouse installation, centered around domestic labor and women’s devalued work. Schapiro’s stylistic experimentation continued to evolve alongside her feminist projects. In 1972, she made her first painting to incorporate fabric: Curtains, which will also be on view. Although this painting initially “frightened” her—likely due to its overt femininity—Schapiro would continue the practice of feminist collage. That same year she would create Lady Gengi’s Maze integrating fabric with illusionistic geometry. With the title, she references Asian art and miniature painting. She depicts three "flying carpets'' hovering over an architectural setting. It is a dramatic combination of the very austere: black and white linear elements, with complex color, pattern and decoration. One carpet features an aperture into space.

In 1976, Schapiro became a founding member of the Heresies Collective, a group of feminist political artists. She co-authored, with artist Melissa Meyer, an article which termed this work “femmage.” “Femmage” was defined with specific criteria, some of which include using remnants or scraps, and including covert imagery.

1976 was also the year of Schapiro’s final exhibition with Emmerich. It is significant that she showed works incorporating lace, needlepoint, floral prints, and items such as aprons. Emmerich, although known as a champion of Color Field painting, had wide-ranging interests, and also mounted important exhibitions of pre-Columbian art. Upon her return to New York in 1975, Schapiro felt the support of the artist community that defined Emmerich Gallery. As Henkin writes, “the Emmerich gallery was not only a commercial venue, but a space where she could experiment, show an ever-evolving practice, and prove herself as an artist.”

Miriam Schapiro’s Abstract Expressionist work is currently on view in the exhibition Action, Gesture, Paint at the Whitechapel Gallery, London; while her femmage painting is on view in the exhibition Too Much is Just Right: The Legacy of Pattern and Decoration at the Asheville Museum of Art, North Carolina. Schapiro’s work is in the permanent collections of museums worldwide including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney Museum, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; and the Museum of Moderner Kunst, Vienna, Austria.