Thomas Sills: Variegations, Paintings 1950s–70s

Eric Firestone Gallery

4 Great Jones Street, 3rd floor, New York, NY

January 19th–March 19, 2022

Eric Firestone Gallery is pleased to present the exhibition Thomas Sills: Variegations, Paintings, 1950s–70s, accompanied by a digital catalog and online viewing room. The gallery also announces exclusive representation of the Estate of Thomas Sills.

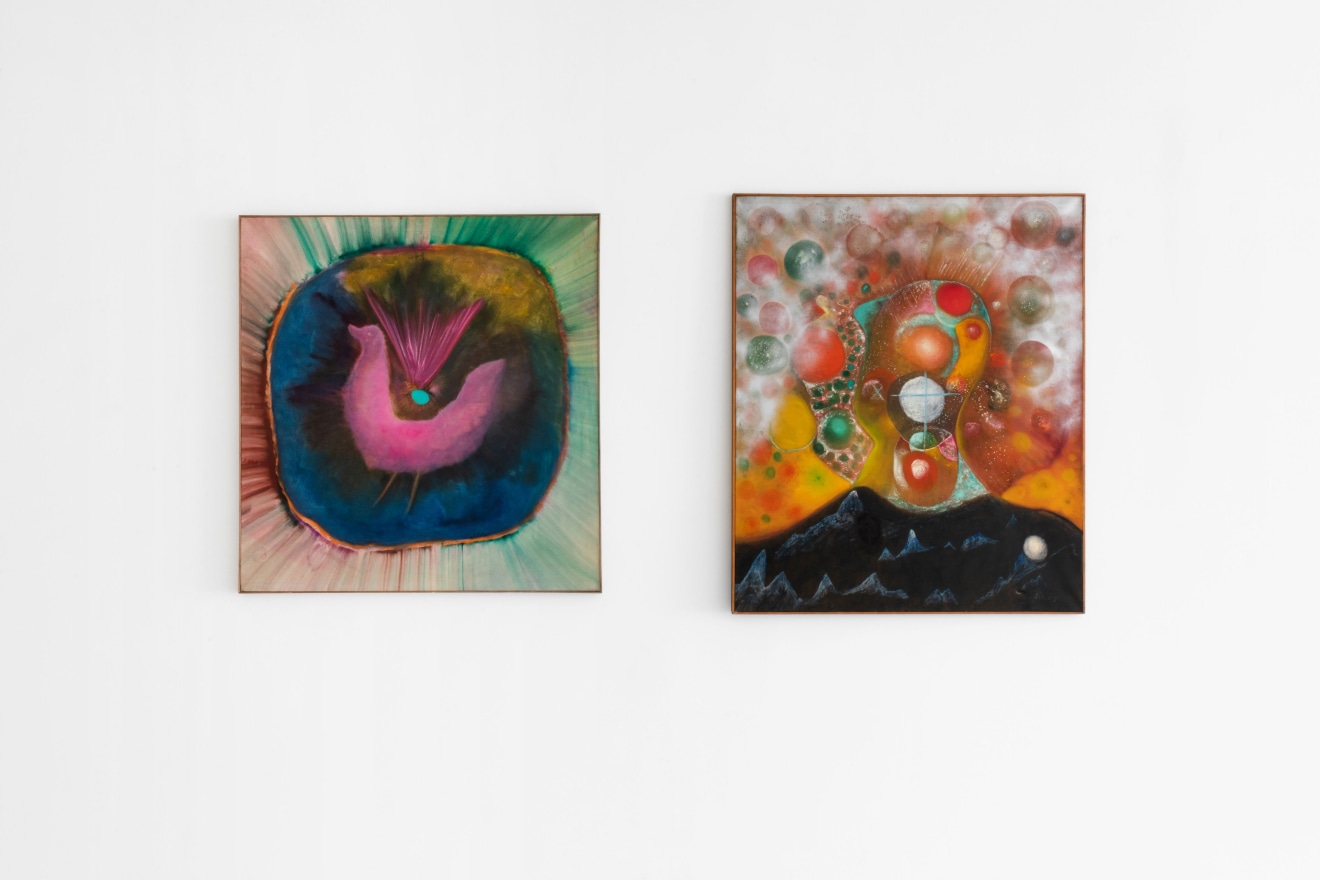

Thomas Sills (1914–2000) was a significant African-American artist who created a major body of abstract paintings that respond to process, natural phenomena and forces. The paintings, which have a delicate and unusual palette, synthesize the figure/ ground relationship with optical equivalencies between colors, and free-flowing, outwardly-radiating patterns.

Sills, who grew up in Castalia, North Carolina in a large family, was not exposed to art or art-making in his youth or young adulthood. He began to paint – almost clandestinely – in his late 30s, and went on to be the subject of four well-received solo shows at Betty Parsons between 1955 and 1961. His work was also acquired by a long roster of significant museums across the country, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, all New York; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

At age 9, in North Carolina, Sills worked after school in a greenhouse – an experience he enjoyed and which he credits as influencing the color and light of his paintings. His boss encouraged him to move north, and at age 11, Sills arrived in Brooklyn to stay with an older brother. He spent the next twenty years working various jobs and starting a family with his first wife.

While working as a superintendent for a church in Greenwich Village, and doing delivery for a neighborhood liquor shop, Sills met artist Jeanne Reynal (1903 – 1983), the mosaicist whose estate Eric Firestone Gallery also represents. Reynal and Sills became involved and married in 1953.

Reynal was a significant figure at the intersection of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism – a patron as well as a radically innovative artist. Through her, Sills met a wide range of artists: from Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst, to Willem de Kooning and Arshile Gorky, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko. Sills was also surrounded, in their West 11th Street home, by her collection of these artists’ work.

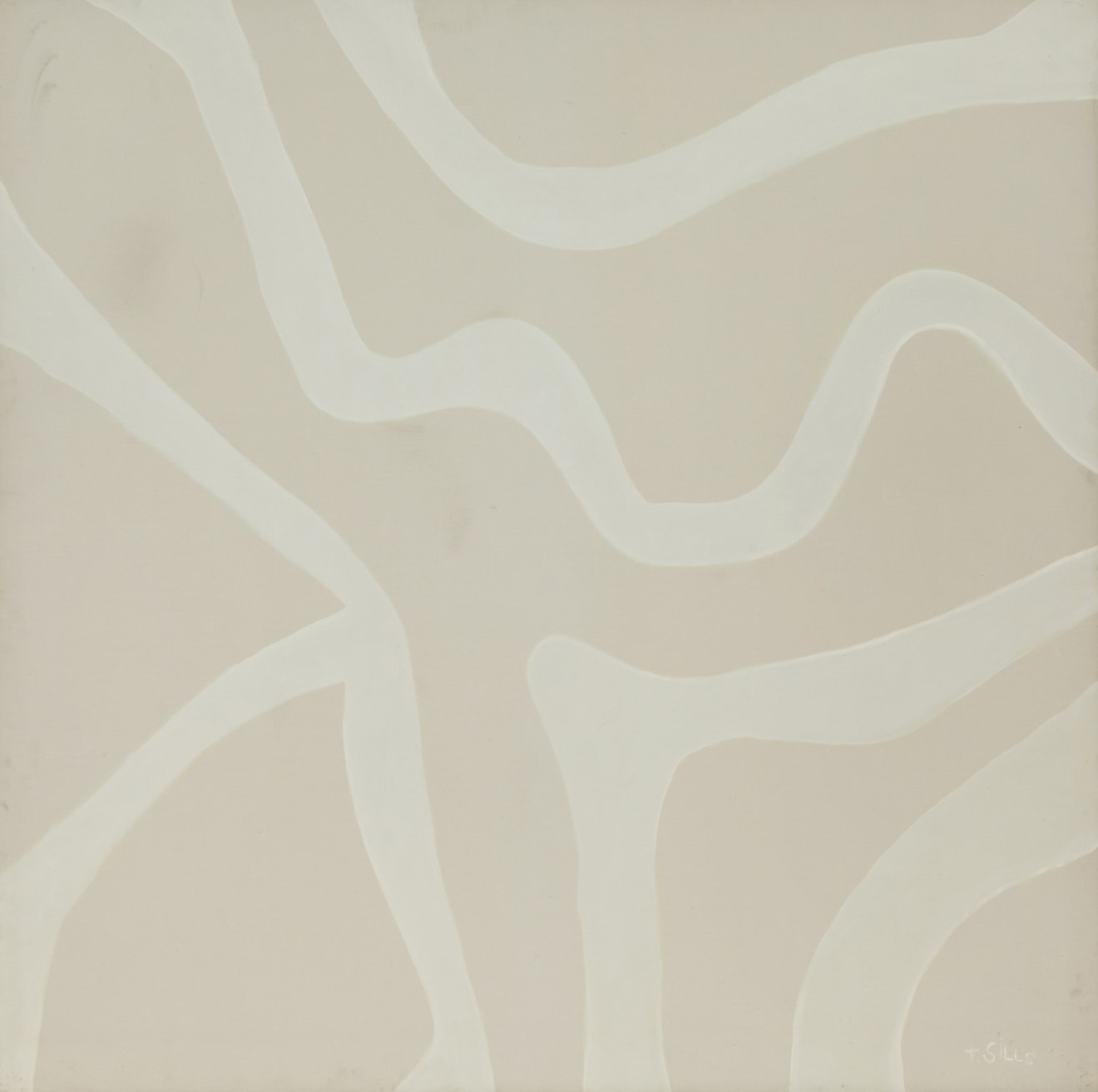

In his first forays into painting, Sills applied magnesite plaster from Reynal’s studio to discarded wood panels. Ideas about surrealist automatism and experimentation resonate in Sills’s early work. He was encouraged by Reynal and by Willem de Kooning to keep painting without any formal study. Sills did not use brushes; instead, he applied paint with rags and cloths. This gives his work a unique softness. Colors meld into one another at the edges, lending the paintings tactility, space, and an inner light.

By 1955, Sills had developed a unified group of paintings with central forms suggesting birds, nests, apertures, nebulae and eyes. These works formed his first solo show at Betty Parsons. They have qualities associated with American visionary painter Arthur Dove. The critic Parker Tyler, in an ARTnews review, described them having “the terror of nightmares with desire and pleasure at their core.” By the mid-to-late 1950s, these allusions dissolved into abstraction. Still, the paintings have an energy at their center which generates movement and radiates outwards.

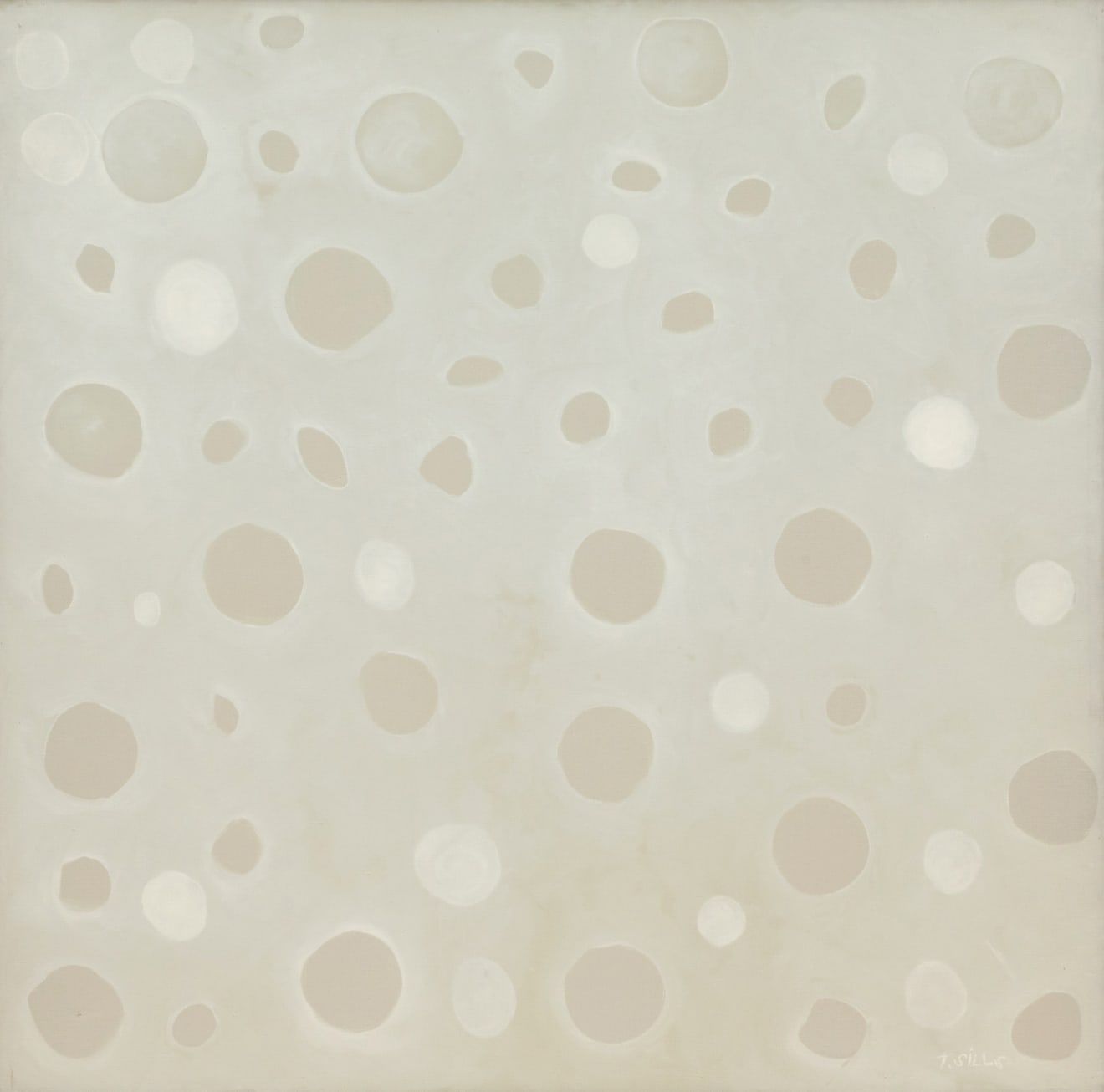

Sills discovered John Graham’s book, “Systems and Dialectics of Art” in the early 1950s. Certain passages, like “The brushstroke ought to be a direct result of the phenomenon observed,” echo through Sills’s unique approach. As the work developed, Sills frequently employed a balance of two or three main colors in each painting. The main forms became bigger, more jagged and earthy. In the mid-1970s, he made a series of “White Paintings” – comprised of forms and shapes painted in beige, cream-tones, light gray, and white.

In addition to his exhibitions with Betty Parsons, Sills exhibited with Paul Kantor Gallery, Los Angeles; and had a two-person exhibition with Reynal at the New School for Social Research, New York. In the 1960s and early 70s, he showed with Bodley Gallery, New York. He was the subject of solo exhibitions at Creighton University, Omaha, NE; and the Art Association of Newport, RI. Sills was also included in several important historic exhibitions of African-American artists in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Lawrence Campbell was the critic of the period who wrote most consistently on Sills’s work. In a small monograph published by the William and Noma Copley Foundation in 1962, Campbell writes: “Sills’s paintings seem profoundly American. Out of them something tender and reassuring seems to be rising. It is like a voice from the people heard above the mass media of our time.”

Sills said of his process:

"The main thing for me when I work is to say something worthwhile. My eyes must be open to see some of the good things. What I think about when I start painting is paint. A painter should paint only the way he wants to paint. There are no rules about it. I try not to destroy what comes out of my paintings. I don’t fight it but let whatever is there, come out."